Great Teams

There have been many great sports teams over the past hundred years. Some have been dominant for stretches of ten years or more. In North American professional sports, the New York Yankees of the immediate post World War II years won the Major League Baseball Championship 10 out of 16 years. The Boston Celtics of the 1960’s were even more dominant. Between 1957 and 1969 that team won the NBA championship every year but one. Amongst college teams, the men’s UCLA Bruins basketball team of the late 1960’s-early 1970’s was probably the greatest, winning seven straight Final Fours from 1967-1973. They are followed closely by UCONN women’s basketball who won 9 of 15 championships in the first 15 years of the this millennium.

Outside of North America, who could forget the Soviet Union National Hockey Team that utterly dominated that sport from the late 1950’s until the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. The famous CCCP team won 19 of 26 world championships starting in 1958 through 1991 and every Olympic Gold in that period except the upsets by the United States in 1960 and the well-known shocking loss to the United States again in 1980, regarded by most as the greatest sports upset of all time. More recently, Manchester United won the English Premier Soccer league a dominant 13 times during the 20 years starting in 1992.

These were all great teams that, measured by championships, were astounding successes. However, if one were to bet on them, even at the peak of their greatness, there would be some bookmaker odds that would be too high. Certainly, on a 1/1 bet - meaning for every dollar you are risking in the bet, you could earn one dollar - one would have taken the Soviets over the Americans in the 1980 Olympics every time. It would not have been crazy to take even 20/1 odds, meaning the bettor would risk losing twenty dollars to earn only a single dollar. What about 100/1 odds? Surely, there was some odds at which betting on the Soviets, no matter how great a team they were, was a bad risk to take. A $100 bet at 100/1 odds that the Soviets would win would have cost you $10,000 when they lost in that historic upset. That risk reward does not seem to be worthwhile, does it? We point this out because a similar calculation should be made with how much one is willing to pay for even the greatest companies. At some point, the risk is simply not worth taking.

How to Define a Great Company

We often hear from clients or other market participants about how great a particular company is and that we should own it (or own more of it). There are no championships for companies, so usually a great company is defined as one that has had outstanding financial performance over an extended period. Others may look at things differently, but to us, a great company is one that takes the capital that is given to it and grows that capital, consistently, at a faster rate than its industry and the market. Is that not what it is all about? As investors we have capital that we need a good return on. We want companies that give us that.

Speculation

These days there is a lot of confusion over many investment issues. Many think a great company is one whose stock price goes up dramatically, regardless of the economic performance of the company. Such a company may make for a great investment, but it does not necessarily mean the company is great. Given the immense amount of liquidity being created by central banks and the low level of interest rates, it is not surprising that a lot of stocks go up (see last month’s "Risk On/Risk Off" for a discussion of the impact of low interest rates on equity values). Unfortunately, the last few decades have seen the easy money policy of our central bankers bail out many bad companies. Oftentimes, these weak companies may go on to climb to amazing stock price heights in an upcycle. As this has happened repeatedly, it seems that many market participants no longer understand or care about the relationship between company fundamentals, economic value, and how that should relate to returns from owning a stock. To those investors, or should we say, those speculators, it is merely a game of guessing which ticker symbol the other guys will buy and drive to a higher price.

The most glaring illustration of this phenomenon was the recent action in Game Stop Inc. (GME) where it appears an informal group on a social media website called Reddit entitled “Wall Street Bets” encouraged members and others to purchase GME. Their goal was seemingly to create a short squeeze that would drive the stock price higher. For a time, they were able to do that. As far as we know there was no thought given to what the stock might be worth. The whole exercise appears to have involved the movement of the stock price of GME devoid of any relationship to the company’s value. This example, albeit extreme, is representative of the mindset of many investors today after several decades of nearly endless easy money. “Buy the dip” has worked so why worry about a company’s fundamentals or its value?

THE Difference Between Return on Equity and Return to Shareholders

“Although there are good and bad companies, there is no such thing as a good stock; there are only good stock prices, which come and go.” - Benjamin Graham

Certainly, speculation can work for periods of time. So too can investing in bad companies if they are priced right. As Benjamin Graham, the father of modern valuation theory said in the quote above, the right price for a company comes and goes, even for bad companies. Over the long term though we think the best strategy is to invest in great companies at good prices. Certainly, there is some price at which great companies are trading at too high a price to make the risk of investing in them justified. Obviously, thoughtful investors rationally pay a premium for a good company over a bad company since the high returns generated by a good company can enable it to grow quickly (see our discussion on this topic). Nevertheless, just as there are some odds a bookmaker makes that are too high even to bet on the greatest sports team, there are valuations that make even the greatest company too expensive.

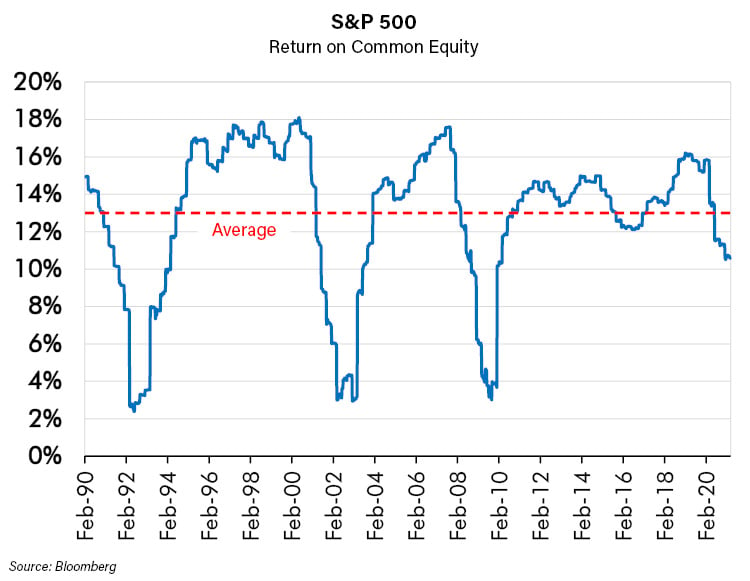

As mentioned above, we believe that most would agree that the paramount metric to judge whether a company is great is whether it makes great returns on the equity invested in it. That is known to financial analysts as a company’s Return on Equity (ROE). It is measured as the earnings divided by the book value of the equity of the company. We look for and screen for companies with a high and consistent ROE number. It is hard to argue that a company with a consistent ROE of greater than 25% is not a great company. After all, who wouldn’t be thrilled with the ability to invest money and make consistent 25% returns, especially in the current environment of meager interest rates on bonds? The S&P 500 in the aggregate has averaged approximately 13% return on equity since 1990 and is now lower as the chart below illustrates.

The problem is that when one invests in a company that makes a 25% return on its equity, the investor is not necessarily getting that 25% return. One’s return as an investor depends upon the price paid for the stock, particularly the stock’s price/book valuation. Let me explain.

The 25% return is calculated on the book value of the equity on the company’s balance sheet. However, the investor is (usually) paying an entirely different price for his or her equity, often paying a price/book ratio higher than one. So, the investor’s theoretical economic return is not the ROE, but the earnings divided by his or her actual cost to buy into that return. We use the phrase theoretical economic return because a passive investor can only realize a return through dividends or selling his or her position in the stock. However, the calculation is important, nonetheless. The theoretical return would not be theoretical to someone who bought control of the entire company. That buyer would get the actual return.

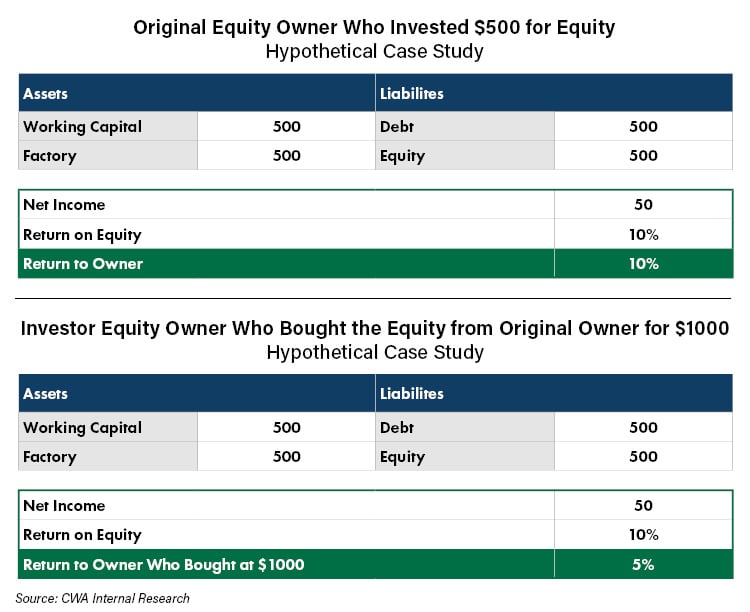

Thus, the actual return is an important guidepost for a company’s value. A firm that earns a 25% ROE makes a very good return. If it were to trade at book value, i.e., one times book value, it is very likely another company would buy it to capture those high returns. On the other hand, if the price of the company were twice its book value, the 25% return would be only a 12.5% return to a buyer. That is still a pretty good return. It would not be crazy for another company to buy that great company for two times book value to achieve a 12.5% return. Therefore, it may make sense for a passive stock investor to buy at that price as well. The following tables show how the math works for a company with a 10% ROE that is purchased at book value in one example and two times book value in the second.

What if the great 25% ROE company was selling in the stock market at 25 times book value? At that price things are getting to be like betting on the Soviets to beat the United States in the 1980 Olympics and paying 50/1 odds. At 25 times book value, the return to a buyer at a 25% ROE would be only 1%. What about 50 times book value? Clearly there should be a price at which one would not buy even the best company in the world just as there are odds one would not take in betting on the best team. At a 1% return based on past ROE, it is not likely that there would be a corporate buyer for that great company unless they saw a way to dramatically increase earnings and therefore the returns from the current level. That is unlikely for a company that is already “great.” For that reason, passive stock investors should not buy at that price either. Of course, that does not mean that the stock price will not go higher – Wall Street Bets members might decide to write about it and send the stock soaring further - it just means a prudent investor should not chase it– no matter how great a company it is.

Conclusion

The point here is to address the issue of the difference between great companies and great stock prices. We hope we have demonstrated that there is in fact a difference. As investors our goal is to create portfolios that outperform at as low risk as possible. To do that we strive to look for great companies at good prices. No matter how great a company is there is some level of price that is too high. This should not be too hard a concept to understand especially if one considers the great teams sports betting analogy described above. However, it seems that many investors do not exercise caution in this regard. It may be simply because the price already may be high and so the current valuation has seemingly already been validated by the market – these investors may think that the company is great; should its price not go even higher? Maybe it will, but in our opinion, a prudent investor looks at the valuation, at what the investor is paying to earn a return and pays less attention to the current stock price. Often the math is simple and clear: a company can be so expensive that it is a bad investment, regardless of how great it is.