Early in my career, during the dot com boom, I covered energy and chemical stocks for a large asset manager. In those days everyone on Wall Street and in much of the rest of the country was enamored with the prospects for the internet. Many young people at the time wanted a career either in Silicon Valley at a startup internet company or they wanted to work on Wall Street in some capacity raising money for or investing in internet stocks. I covered wireless and cable companies at the time, in addition to energy and chemicals, so I did have a foot in the door of technology but I tended to spend more of my time on the commodity sectors. Having studied a lot of economic history, I believed in cycles and thought being a commodity analyst at a time when commodity investing was out of favor would create opportunities in the future when the group rebounded.

During that time, I happened to catch a late night television showing of the Graduate, a film released in 1967 starring Dustin Hoffman in the role that made him a household name. Most of the readers of this publication have probably seen it. The movie, inflation adjusted, is still in the top ten highest grossing films of all time. It is ranked as the seventeenth best movie of the twentieth century by the American Film Institute. In the movie, Hoffman’s character, Benjamin Braddock, is struggling with the direction he is going to take with his adult life after his recent graduation from Williams College. There are many memorable scenes in the movie, but to most, the scene where Anne Bancroft’s character, Mrs. Robinson, seduces Benjamin Braddock is the one that stands out. Not to me, I was a chemical analyst at the beginning of my career. The most memorable scene for me was when Mr. Mcguire, a family friend, pulled Hoffman’s character aside to give him career advice. He said “If I just say one word to you, are you listening? Plastics … great future in plastics”.

The scene resonated because, at the time, nothing could have been further from good advice. If the movie had been made in 1999 the advice would have been “internet” . . . certainly not plastics.

Plastics are derived from hydrocarbon based chemicals primarily either Ethylene or Propylene. Plastics are the primary end product of the petrochemical manufacturing process. Ethylene and Propylene can be made from either crude oil or natural gas. The hydrocarbon feedstock is by far the biggest component of the cost of production. Whether a chemical company chooses to build a chemical plant that uses oil or natural gas as its feedstock is almost exclusively dependent on which commodity is cheaper in its region. For decades natural gas produced in and around the Gulf of Mexico was cheaper than oil. So, in the 1950s and 1960s, when the Graduate was being written and plastics was a growth industry, the United States chemical industry on the Gulf Coast grew. It was a good place for a college graduate to go to start a career. Not so much by the late 1990s. At that time natural gas prices were high relative to oil so the plants along the Gulf Coast were at a cost disadvantage. What was worse was that over the decades since the US chemical industry heyday, Saudi Arabia and other countries in the Middle East became far more sophisticated about driving value from their natural resources. As everyone knows there is plenty of oil in that part of the world. In fact, most of the oil is there. There is also a lot of natural gas that is produced as a byproduct of that oil (referred to as "associated natural gas"). However, up until the last few decades of the twentieth century, given how far that gas was from demand centers in Europe and Asia it had no value. It was simply flared away.

However, as they became more sophisticated, the Saudi’s and others in the region realized they could use that gas to make Ethylene and other chemicals. Given that the gas was essentially free, they would be able to make chemicals very cheaply. So, they built a lot of chemical plants and became the world’s low-cost producer. United States plants, with their high cost gas, could barely survive.

What is a Cost Curve?

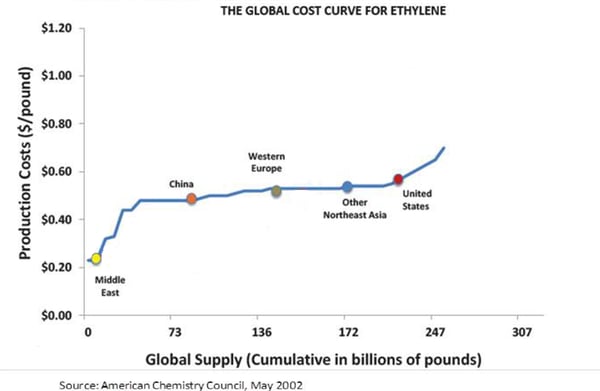

We have talked about and explained the concept of the cost curve in our publications before. It is a very important concept that sounds complicated but is really quite simple. It is just the supply curve that is taught in high school or freshman year college micro economics. A certain quantity of every commodity type product can be produced at particular prices (costs) with the lower prices (costs) showing on the lower left and higher prices going up and to the right. It’s importance to investment decisions is that companies that are at the bottom of the cost curve, i.e., their costs are low relative to their competitors, can make money in tougher economic environments when prices are under pressure. Higher cost companies often lose money in those scenarios. For the same reason low cost companies make more money than their competitors in good times when prices are high. In the late 1990s United States plastic production was very high on the cost curve, as is illustrated on the chart below.

It is worth noting that the production from plants along the Gulf Coast were not only disadvantaged due to the nearly free natural gas in the Middle East and lower cost oil-based feedback but also due to the fact that the new lower cost plants were much closer to the fastest growing markets in the world in Asia. The transportation cost advantage was an added detriment to the North American industry that is not included in the graph above.

So, if Mr. McGuire told Dustin Hoffman’s character to go into plastics as a career in 1999, it would have been horrible advice. As analysts we were writing the industry off.

The Shale Revolution and the Revival of the United States as Low-Cost Producer

Fast forward to 2018 and the advice from the Graduate might not be so bad after all. The shale revolution unlocked copious amounts of cheap natural gas in North America. On an equivalent unit of energy, domestic natural gas is now far cheaper than oil. The current price of natural gas is $3 per mcf. Its equivalent price to the same amount of energy produced by one barrel of oil is $18. That compares to Brent crude oil at $84. Oil is nearly five times as expensive as natural gas!

It is important to keep in mind that much of the world does not have a free market for natural gas. Long term contracts have tended to be based off the price of oil. So, at current prices for natural gas, energy in North America is cheaper than energy in most of the rest of the world. A second important technological revolution has contributed to that. The lowering of the cost of cooling and liquefying natural gas so that it can be shipped around the world. This made the natural gas that was produced in the Middle East worth something …. Usually worth closer to the value of oil since it was priced off of it.

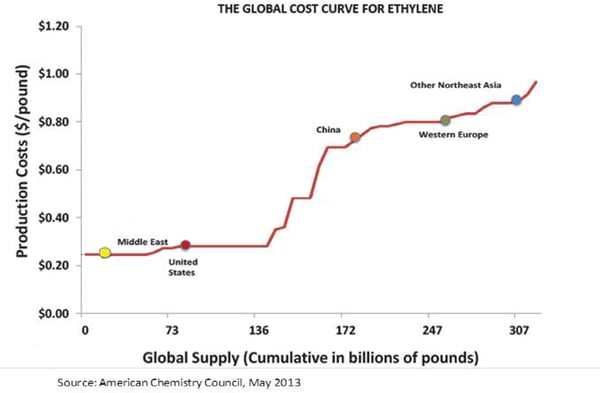

So, all of a sudden, chemicals (and thus plastics) were nearly as cheap to make along the Gulf Coast as in the Middle East and they were much cheaper than the oil-based production elsewhere. The United States dropped to near the bottom of the cost curve as shown in the chart below.

Given the continued prolific production of shale gas and associated gas from shale oil, especially in the Permian Basin of West Texas, we expect this situation to persist for a long time.

How Can Investors Benefit?

After some nearly 20 years of shunning the United States chemical sector, we suddenly find that we agree with Mr. McGuire . . . we should be in plastics (or at the very least, chemical related companies). When priced appropriately stocks in chemical companies may be good investments. However, due to less cyclicality, steady dividends and reasonable balance sheets, we often prefer exposure through the value chain of the industry. We wrote several months ago on pipeline companies. These companies are benefiting as the natural gas and related products need to be transported to new or expanded chemical plants. Many of these companies also gather, process and fractionate natural gas. Processing and fractionation are the methods used to separate the natural gas used for heating and power plants from the liquid forms that are best used for making plastics and other pretrochemical products. Given the low cost, many companies are now even exporting the natural gas and chemical raw materials around the world. For this reason, certain transport companies remain under our watchful eye for when they are priced appropriately.

Conclusion

Looking for the next growth industry, be it plastics in the 1960s, the internet in the 1990s or smart phone-based products and services today can be lucrative. However, unless you recognize the opportunity early it is often difficult to succeed with these crowded and hyped investment trends. Paying attention to mature businesses that are undergoing structural change may often be an easier place to find value. We are looking carefully at a whole range of businesses that are benefiting from the secular change of North America into a low cost energy producer. The chemicals value chain is at the front of the list in that regard. Plastics! Not such bad advice from a classic movie from long ago.