“It is better to have a permanent income than to be fascinating.” - Oscar Wilde

“The best safety lies in fear.” - William Shakespeare

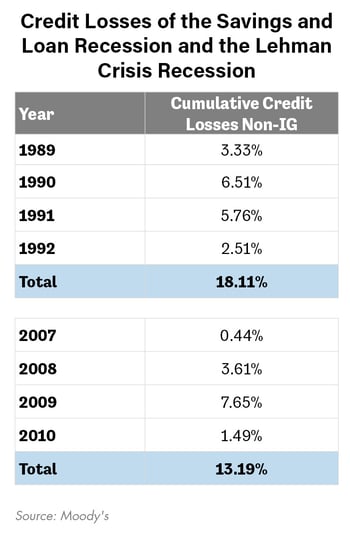

In the early 1990’s there was a serious recession brought about by what has come to be known as the Savings & Loan Crisis. It was that period’s unwinding of too much credit and other excesses of the financial industry (often from Savings & Loan companies, which are bank like entities, thus the name of the crisis). The preceding expansion coincided with the presidency of Ronald Reagan and is generally attributed to his economic policies such as lower taxes, lower regulation and lower government spending. This was all, presumably, enabled by a Federal Reserve Board, which, under Paul Volker, vanquished the high inflation of the 1970’s with tight monetary policy early in the decade thus allowing interest rates to begin falling . . . a trend that is still in place today. However, an alternative explanation of the boom and bust, which we ascribe to, is that the 1980’s was a typical credit cycle enabled by Keynesian like fiscal spending and junk bond and Savings & Loan fueled debt. It ended when excessive debt service requirements ran up against reluctance by central bankers to continue fueling the expansion. By at least one measure, that recession was worse than the Great Recession in 2008, which we will explain in more detail below.

The recession hit the financial industry in New York very hard. There were widespread layoffs at investment banks and related services, especially law firms. I had the unfortunate luck of starting my corporate law career at the time. I started in September 1991 at a large New York law firm which was about to downsize along with most of the industry. I was lucky to have a job. Being a first-year associate at a mega law firm is extremely tough under any circumstances, but it was particularly tough then. We were all scared of losing our new jobs. Many of my classmates at Fordham Law School had employment offers rescinded prior to starting work at the end of the summer after completing the bar exam. Many others never found jobs at all during our third and final year, the 1990-91 academic year. The partners at my firm were not particularly sympathetic to our plight and made sure that we understood how lucky we were to be employed at all. Theoretically we were budgeted to bill forty hours per week to clients. This alone would have required many more hours of actual work than forty, especially during a recession when many days there was no client work to be done, which did not absolve us of the responsibility to do work for the firm. In actuality, the partners expected much more than 40 billable hours per week. An associate who wanted to move ahead needed to average between 50 and 60. To get to those numbers and to make up for non-billable hours, when assigned to a deal we were required to spend well over 100 hours per week working. In fact, we were required to work however many hours we were needed. On a deal we were needed a lot. Towards the end of public offering deals junior associates were required to be at the financial printer non-stop to get the prospectus and similar documents perfect and ready for publication. Sometimes this required 48 hours or more of non-stop work. I recall a telecommunications Initial Public Offering that I was assigned to where I was at a printer’s office in Dallas without sleep for nearly three whole days. I then got a few hours break before another 24-hour stint.

A Permanent Income from Savings

It was grueling. We all wanted to quit at one time or another. For the first time in my young life I seriously thought about how much money one would need to retire. Boy, did myself and all of my fellow associates fantasize about retirement! In our downtime at 3 am sitting around a conference table we talked about how much money we needed to accumulate to be able to quit and still live the way we wanted as twenty somethings in New York City. Keep in mind that we were in our mid-twenties in New York earning what many of our peers considered to be outrageous money. When we entered law school, we thought upon graduation we were going to be partying in New York city as wealthy professionals. The reality was far from that.

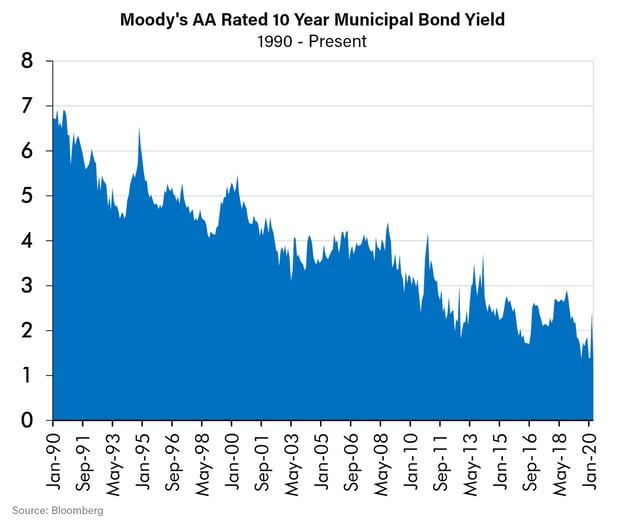

So, how much savings did we need to be able to quit our jobs and enjoy New York City? A first-year law associate earned about $85,000 per year then, which was more than enough to live comfortably as a single person at the time. I figured out that $2 million was the number that I needed to quit. At that time AA muni bonds yielded more than 6% tax free. So, after rolling 3% back into principal to protect against inflation, with $2 million a first-year associate would be left with more money after tax than he or she was earning at their job. So, the fantasy during those long nights at the printer eating lousy catered food and checking hundred plus page prospectuses for typos was to get ahold of $2 million and quit.

Is a Safe Permanent Income Attainable Today?

These days we have many investors we know are after essentially the same thing. They have already quit their jobs albeit after a lifetime of capital accumulation, not in their mid-twenties to party in New York City. What they want to know is that they will have a steady safe income to depend upon so they can live the way they are accustomed to for the rest of their lives. Many are far more interested in that than in growing their capital in the stock market or in other, perceived risky ways. All have lived through the last two stock market declines and most remember the 1990-92 and earlier ones as well. Most understand that 6% tax free in AA credits is not a possibility any time soon. There are few with that illusion. However, it has been my experience that far too many yield seeking investors are unrealistic about what is attainable at the level of risk they are willing to bear.

In 1991 AA muni bonds were very safe, even safer than they are today. Certainly, far fewer state and local governments had the fiscal imbalances they have today and the best of those, the AAA and AA rated credits, had none. But safety is relative. We are comfortable with the safety of most AA rated bonds from the perspective that the holder is highly likely to get his or her promised interest payments and principal returned. However, that does not mean AA bonds have no risk. There is of course inflation risk and in an uncertain world there is always some default risk, even if it is small. In addition, longer term bonds have duration risk. If interest rates rise the value of longer dated bonds decline.

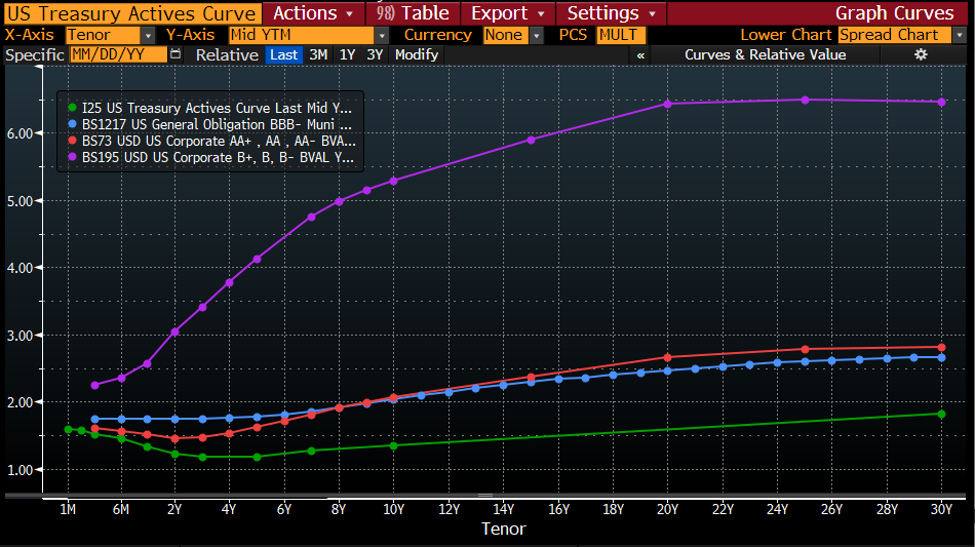

Remember though, the objective for many retirees, is to live off income generating securities. None of us know when we are going to die, so one needs to plan for the income to last a long time and to not be destroyed by inflation. The following chart shows the problem.

Source: Bloomberg

What it shows is the available yields of different types of bonds at different maturity dates. The blue line is low investment grade municipal bonds. Even those yield a mere 2% for a 10-year bond, although, thankfully, that yield is tax free. If one assumes inflation is 2%, which is near its medium-term average, 2% tax free leaves you with zero yield. That is not something first year law associates can fantasize about let alone retirees who really need to live on their savings. As the chart illustrates, other taxable safe yields are similar.

Stretching for Yield and Ignoring Safety

The highest yields on the above chart are the 7% achievable in below investment grade corporate bonds and those levels are only achievable if you buy longer dated bonds with duration risk. Similar yields are available on equivalent rated municipal and other types of bonds. One can likely achieve an after-tax yield of around 4.5% and have roughly 2.5% to live on while fighting off inflation. However, even in such a scenario, where there is no risk, many investors with $2 million of savings, or even $5 million for that matter would have a hard time living comfortably off of the $50,000 - $125,000 after tax income generated.

Investing is about managing risk and making wise choices. In the case of less than investment grade bonds, there is a higher risk of default versus other alternatives. As noted in the first paragraph, the Savings & Loan Recession was quite a bit worse than subsequent recessions on one important criterion: credit losses. Credit losses are the losses incurred when a bond defaults. If a bond with the obligation to pay its holder $100 at maturity defaults and in bankruptcy the holder receives $50 there has been a 50% credit loss on the bond. Below shows the credit losses of the Savings and Loan Recession and the “Great Recession” that accompanied the failure of Lehman Brothers.

As noted above, history shows examples of losing nearly 20% of your principal forever on less than investment grade (high yield) bonds. Of course, the Great Depression data would be even worse were it available. So, for the additional approximately 5% yield to be picked up by purchasing riskier securities, an investor could lose four or more times that amount in a downturn. Not much for a reliable income.

The story is the same with most publicly traded securities that have high yields. Certainly, there are equities, Master Limited Partnerships and Real Estate Investment Trusts with even higher yields, but the risk of principal loss as well as dividend cuts are real. We think it is reasonable to assert that higher risks accompany higher yields.

In addition, its useful to note that when our team analyzes inbound portfolios from other advisors, we often see leveraged closed end funds. Our fear is that many investors hold these securities not understanding where the yields came from: leverage. A fund that invests only in “A” rated credits that is levered 40% may have a current yield at 6%, but the fund post-leverage most likely could not earn an “A” rating. We think it is wise to be wary of those! Our advice is this: know how your yields are generated.

Conclusion

Although miserable and over worked first year law associates usually get over their desire to quit their jobs and retire in their twenties, real retirees are understandably always interested in a steady income. Certainly, we frequently are asked to provide more income in portfolios we manage. It is an understandable goal. However, given current interest rate and risk conditions it is difficult to attain the level many investors want. Our risk management discipline often limits the income levels we are comfortable designing into model portfolios. We see many inbound portfolios from other advisors that appear to be in a headlong pursuit for higher income. We think this strategy may have hidden risks that are only fully understood during a downcycle. As Johann Von Goethe, a noted German writer and thinker from the late 1700’s said, “The dangers in life are infinite, among them is safety”. It is the hidden dangers of seemingly steady yield that we are trying to avoid, while also providing for our investor’s desired income.