Chief Conclusion

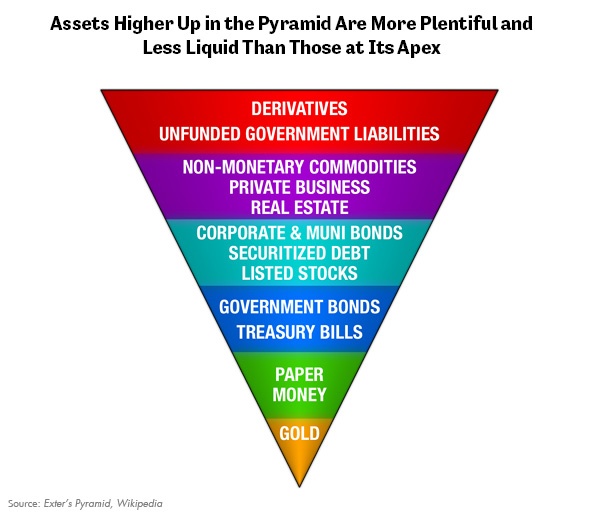

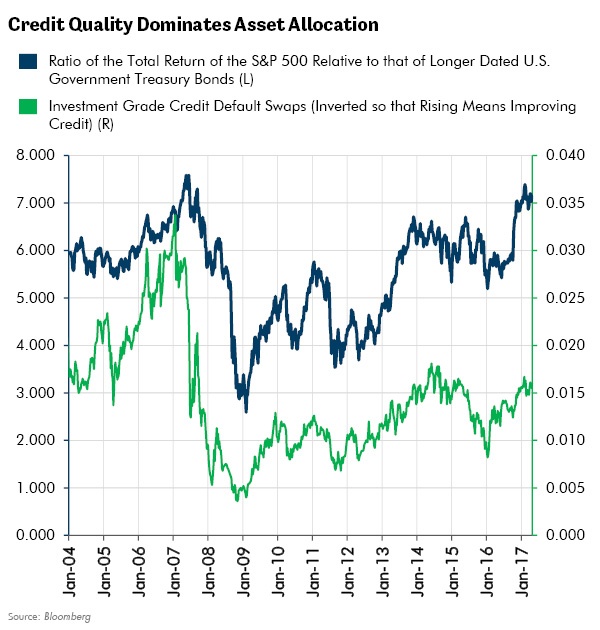

When danger rears its head, the mass of capital flees riskier assets to crowd into the much smaller quantity of safer assets, which drives up their price. Worsening credit quality, best expressed in the credit default swap market (CDS), is the catalyst. Exter’s Inverted Pyramid demonstrates these forces in action, helping to explain the merits of U.S. treasury bonds as an equity hedge.

I write “Trends and Tail Risks” to help explain our investment team’s framework, and our investments, to our clients and friends. Many topics recur again and again, focusing on the miracle of the market’s use of price to bring supply and demand into balance.

Understanding supply and demand for financial instruments is just as important as understanding it for commodities and other goods. Our team is focused on understanding the supply and demand of financial instruments so that we can harness the power of volatility to the benefit of our portfolios. Many times these pages have touched upon the role of longer-dated, U.S. government treasury bonds, as a particularly valuable hedge for an equity-laden portfolio. Today’s “Trends and Tail Risks” is meant to tie these threads together, which is best done through the framework of John Exter’s “Inverted Pyramid.”

John Exter: Distinguished Student of the Gold and Credit Markets

John Exter was a brilliant thinker with a long and distinguished career in global finance and monetary policy, including time as an economist at the U.S. Federal Reserve and as the founding Governor of the Central Bank of Ceylon. Mr. Exter co-founded the Committee for Monetary Research and Education (CMRE) in 1970 with other leading economists such as Henry Hazlitt, Jacques Rueff, and Robert Triffin. They were worried about the collapse of the monetary system of their day – Bretton Woods. Just a year later, their fears were realized in August of 1971. Exter became a very wealthy man when he profited from his early and controversial insights by investing heavily in gold which rose dramatically after Nixon suspended convertibility of foreign dollar reserves into gold thus effectively ending the Bretton Woods system.

I first came across Mr. Exter’s work a decade ago, while attending a meeting in New York of CMRE (yes, I am a finance geek). What I found remarkable about Mr. Exter’s work was his unique perspective on gold. The CMRE is a home for some of the more thoughtful research on gold – and the credit markets – but Mr. Exter’s view was different from that of any other analyst, for two reasons. First, Mr. Exter believed that a credit-driven expansion was ultimately deflationary due to continuously rising claims on future cash flows. This view made him unique among all other gold market observers. Second, he developed a simple heuristic, the inverted pyramid shown below, to illustrate this process at work.

Exter’s Inverted Pyramid

His pyramid stands upon its apex of gold, which has no counterparty risk nor credit risk and is very liquid. As you work higher into the pyramid, the assets get progressively less creditworthy and less liquid. For instance, paper money here means cash, which is recognized everywhere but is ultimately dependent upon the creditworthiness of the U.S. government. Farther up the pyramid, we find longer-dated U.S. government debt, which like cash is dependent upon the full faith and credit of the U.S. government – but on a longer time horizon. The next level is debt of municipals and corporations, whose value is more safely assured than that of more junior claims, such as investments in stocks, the junior tranche of a corporation’s capital structure. A rough estimate of the global liquid financial markets would place their value close to $100 trillion. This number grows further still as less liquid assets are added, such as private businesses, real estate and ultimately bank derivatives, the largest and murkiest of all assets.

Capital Flows in the Pyramid as the Cycle Changes

During an expansion, capital shuns the lower returns, greater liquidity, and safety of the pyramid’s apex to seek more profitable, but riskier, employment in less liquid markets up the pyramid. The longer the expansion continues, the more extended this pyramid becomes.

Once credit quality starts to worsen, however, this bloated structure pancakes back down upon itself in a flight to safety. The riskier, upper parts of the inverted pyramid become less liquid (harder to sell), and – if they can be sold at all – change hands at markedly lower prices as the once continuous flow of credit that had levitated those prices dries up.

Panic may set in as investors who did not recognize their dependence on readily available credit flows stampede out of this huge pool of assets, trying to cram through the very small door that leads to the much smaller pool of safer assets down the pyramid, such as U.S. government treasury obligations. The supply/demand mismatch happens when sellers of $100 trillion of global financial assets try to find a safe home in the $1 trillion of longer dated (25 years or more) U.S. government treasury bonds, or the $1.4 trillion in investable gold coins and bullion, or the $1.5 trillion in U.S. Dollar physical cash.

Exter’s Inverted Pyramid at Work: Changes in Credit Quality Drive Relative Returns of Stocks versus U.S. Treasury Bonds

The credit default swap market (CDS) is the most sensitive market available for determining where we are in the cycle of credit quality. We use Bloomberg’s index of Investment Grade CDS to monitor this.

When credit quality is improving, riskier investments in stocks tend to outperform U.S. longer-dated treasuries. However, while credit quality is deteriorating, U.S. government bonds often outperform stocks. U.S. government bonds of the longest duration can have the strongest performance, as the chart below illustrates. You should find the same relationship if you looked at the relative performance of stocks versus gold during these times of rising stress.

In Conclusion

We monitor the health of the credit markets because of the insight they contain on the optimal allocation of stocks versus bonds. Why? Our goal is to safeguard our investors’ capital against the worst ravages of an equity downcycle. We want to own the right assets at the right time. Once credit quality begins to worsen, safer assets, such as those toward the apex of Exter’s Inverted Pyramid, should outperform equities.

Our practice is that the deeper we get into an extended economic upcycle, the larger our precautionary holdings become in investments that we believe act as equity hedges. The best hedges we have found so far are longer dated U.S. government treasury bonds, and other select investments about which we have written over time. We are always on the lookout for more.

We seek to change our mix of investments in equities and bonds as the cycle changes. Right now in the later innings of our extended equity bull market, a conservative course of action is to reduce equities to buy more U.S. government treasury bonds, particularly when signs are building of a downturn in the inventory cycle.

These bonds are bought to be sold. Our longer term plan is to sell these bonds at a profit during the next recession to buy depressed equities after capital has fled them seeking the safety of other assets, such as our treasury bonds. Exter’s Inverted Pyramid is one of the tools we use to guide our understanding of this process.