Another meeting of the Board of Governors of the U.S. Federal Reserve has come and gone and still short term interest rates remain nailed to the floor. It’s been a full seven years that they have remained so. Since 2008 we have witnessed “unconventional” monetary policy including “quantitative easing (QE)” or large scale buying of bonds by the world’s central banks. Clearly the world in which we as investors have been living since 2008 is very different from the world we knew before then. The Fed’s estimates for both growth and inflation have consistently proven to be far too optimistic. Yet many observers, including the Fed, continue to expect a return to the way things used to be.

Accordingly, the Fed’s estimates, and those of the market, for the path and level of interest rates have proven to be very wrong in retrospect. Is it finally time, after seven years of effectively zero interest rates, to say definitively that something changed in 2008, and that those events still impact today’s markets? If so, what did happen and what does it mean for today’s investors? In the last few days a number of well-respected bond market observers have commented on this issue. Today’s “Trends and Tail Risks” examines these recent events to ask the question of what it all means for today’s investors.

Is the Fed Mistakenly Ignoring Wise Counsel? Or is the Fed Responding to new Political Pressures? Much is Riding on the Answer.

Well-respected bond market observers, such as Ray Dalio and Jeff Gundlach are publicly wondering if the Fed somehow has it all wrong. Certainly the Fed’s overly optimistic expectations for growth and inflation do not inspire confidence. Mr. Dalio, whose comments I profiled in the last edition of this publication (Equity Market Volatility (Finally) Catches up to Credit Market Volatility, September 9, 2015) is concerned that the Fed does not understand the dangers presented by what he describes as an end to the long-term debt cycle, a cycle that has driven so much of the economy since Nixon de-linked the value of the U.S. dollar from gold in 1971. In fact, Mr. Dalio believes that the next big sustained policy move out of the Fed is not a sustained period of interest rate hikes but rather of renewed stimulus such as another round of QE. Mr. Gundlach, in a recent presentation, asked repeatedly “why hike interest rates?” as he pointed out the weakness in commodities, emerging markets, junk bonds, and inflation expectations. Mr. Gundlach, like Mr. Dalio, also sees no compelling reason for the Fed to raise interest rates.

Is the Fed really just hopelessly optimistic about growth and inflation? I am starting to wonder if perhaps another imperative lies behind the Fed’s failing rhetoric. Could the answer be as simple as: the Fed is now entangled in the same increasingly hostile and polarized political environment we see unfolding around us? The Fed definitely saved the market and wealthy investors with its unconventional measures during the 2008 crisis. But middle class America since then has not enjoyed the same degree of benefits. Is a political backlash growing against the Fed and politics as usual? When I survey the world the answer appears increasingly to be “yes.” If so, then we may indeed need to prepare ourselves to operate in a very different world, one that is experiencing a step function change, where the very rules of the game are changing. Such environments are always the most challenging to navigate – but also the most rewarding for those who can do so successfully.

Is Politics, at Long Last, Starting to Reflect the Changes we have seen in the Markets Since 2008?

In prior editions of this publication, I have outlined the risks of a growing rift between the haves and have nots – between creditors and debtors (Greece: War of Creditors vs. Debtors, July 15, 2015). Creditors, especially the most wealthy, are far outnumbered by the larger portion of the population who are debtors. As the gulf of wealth inequality between creditors and debtors has widened, so has political unrest. This is to be expected.

Democratic societies look to their governments to address the economic problems of the majority. Right now those problems are 1.) low growth, 2.) high levels of public and private debt, 3.) stubbornly high joblessness and extended periods of unemployment and 4.) a loss of confidence in the middle-class American Dream of a better life for their children and a comfortable retirement. These problems are not just in the United States, far from it. Mainstream democracies all over the world are losing credibility in the eyes of their voters. The people are crying out for solutions but none are forthcoming from traditional politicians and their governments. Hungry for an answer, voters are turning away from the center to the political fringe.

It’s my personal belief that the government cannot and should not be expected to be the source of these “solutions.” But democracy ensures each person a vote. There are more debtors than there are creditors, no matter how wealthy and powerful the smaller number of creditors may be. The foundation of democracy is majority rule.

The ongoing failure of traditional politicians and centrist democracies to earn credibility in the eyes of the majority of voters is destroying the political center. This destruction opens the door for an angry and frustrated electorate to seek out answers from the more extreme voices on the left and right ends of the political spectrum. Look no further than the current U.S. Presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. Does anyone really think that these candidates would ever be considered seriously if the economy was strong and confidence in our collective future was high? To me the answer is clearly “no.” These candidates are a reflection of our challenging times.

The Politics of the 1930s are Back: the Return of Communists and Fascists

Make no mistake: this trend is global. Traditional politicians with traditional policies are failing to meet the demands of their voters, regardless of what you or I might think of the merits of those demands. Moves to the political extremes are underway in Hungary, Greece, Spain, Italy, Australia, France, and England, just to name the most obvious examples. Countries with weaker political institutions, especially those in emerging markets, are now suffering extreme duress. Their institutions have buckled under the pressure. Capital flight is the result. No doubt the strength of the U.S. dollar over the last few years is just another manifestation of this global trend, as global wealth seeks a safer haven as property rights come under siege due to the global trend of rising political unrest.

Here my thinking has been highly influenced by Paul McCulley’s brilliant work from 2004 “History Lessons for 21st Century Investment Managers.” Mr. McCulley, a former economist with PIMCO, was especially insightful as he looked into the future and foresaw a world where voters’ sense of “equity and justice” shrank and, in shrinking, threatened the property rights that are the bedrock of capitalism. The best guarantor of stable property rights is a contented electorate. I would argue that today’s electorate, globally, is anything other than contented. Creditors take note!

In what other ways does this trend of political unrest express itself? Wouldn’t it make sense if rising political uncertainty led to falling confidence, falling investment, and hence lower real growth? Isn’t it only natural for today’s corporate leaders to look with foreboding into an increasingly uncertain future clouded by regulatory and monetary policy volatility, and become more cautious? Can we find a financial expression of this political reality in the markets? I believe the answer to these questions is “yes” as I explain below.

Financial Implications: The Global Secular Decline of Real Interest Rates

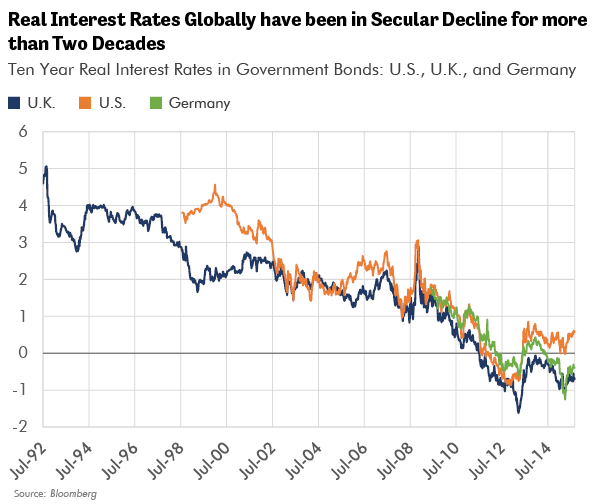

Of all the indicators in the financial markets that I study, the one that I most often ponder is real interest rates. Below I show a chart of the long-term trend of real interest rates since 1992. The trend is decidedly down, with lower highs and lower lows since the data began in 1992. Let me explain.

Here I define real interest rates as the nominal bond yield of government debt obligations minus the market’s inflation expectation for a period that matches the maturity of the bond. I can now clearly monitor inflation expectations thanks to the innovation of the inflation linked bond (TIPS). This allows us to observe the market’s real-time expectations for real (inflation adjusted) returns in the future. The chart below shows the level and trends of real interest rates in ten year government bonds for the U.K, the U.S., and Germany. Please note that the secular decline is global and that real yields in both the U.K and Germany are already negative for the next ten years.

The multi-decade message of the markets is that future real financial returns are falling. Might these trends interact in unanticipated ways with rising political unrest and the failure of the democratic center? If so, then it’s not hard to imagine a future increasingly defined by rising financial volatility and rising political uncertainty. Is it a stretch to believe that these trends could unite to undermine confidence and further lower real growth? Certainly that seems plausible to me.

What is the Right Investment Strategy for Such a World?

The world that I outline above is not an easy world for investors to navigate. As always, a diversified portfolio of high quality dividend stocks and strong bonds, in stable countries is a good place to start. I continue to keep a wary eye out for more signs of increasing credit weakness in the U.S., which has been a focus for the last year and has helped us to avoid many dangers. I share Mr. Dalio’s concern that the next sustained trend in Fed policy could be easing rather than the much-anticipated tightening. The catalyst for this, whenever it comes, should be pervasive U.S. credit weakness that sparks the beginning of a new round of currency depreciation. For this reason our portfolios retain exposure to gold, most especially through the gold royalty companies.

The highest quality, longest duration bonds have earned our favor in the past few years as part of our strategy to capitalize upon the secular trend of falling real interest rates. Such bonds allow us to lock in higher returns for longer out onto the curve while benefiting from capital appreciation as expectations for future growth and inflation fall. I have chosen to avoid, at this point in the credit cycle, the promise of higher returns available to those who may choose to loan money to riskier companies. I fear this promise will prove to be elusive for many investors in low-quality bonds. I still patiently await a time when greater credit stress will create compelling bargains in lower quality bonds. That day is surely coming. But it is not now.

Above all I think the watchword of the day must be vigilance! Vigilance for the risks that lay behind an interconnected world, where the old boundaries between politics, economics, and finance have vanished, and new realities may dominate the old rules. Napoleon was right: history is written by the winners. Are we now in the painful transition that he described from the old political status quo to something new and different? Thoughtful investors would do well to watch the weakening of the democratic center and the rise of the political fringe. It has taken a long time since 2008 for the markets’ new realities to finally find expression in politics. That delay is now over. The political mills have indeed ground slowly. I fear that they will grind exceedingly small. •