Chief Conclusion

The market is a humiliation machine. When you are being the most rational, the market makes you look the most stupid. This is not a bug, it’s a feature. Why? Because the rational pursuit of investments with the least risk and highest reward will lead you time and again to invest in opportunities the market does not yet favor. Make no mistake: to invest rationally is to court humiliation.

Often these unpopular investments have a recent history of poor performance. That is their past but what matters, of course, is their future! We seek out purposefully such ideas because their low valuation and downbeat expectations about their future limit our risk of loss. So when we make investments that seem at odds with conventional thinking, remember that we do so purposefully, trying to wrest the best risk-adjusted returns from the market. We take these risks not because we are “contrarians” but because we are realists. We go where the math leads us in our pursuit of the best risk-adjusted returns, even when that leads us straight into the heart of the humiliation machine.

There are certain things I refuse to do. I don’t skydive. I won’t play Russian Roulette. I have no interest in climbing Mount Everest, even though “it is there.” And I have never, nor will I ever, play the lottery.

There are surely some that would judge me as lacking in heroism or romanticism. To me, however, it’s just the application of rational thinking. I just can’t make the math work.

Many in our society lionize heroic failure, no matter how misguided or ill thought out. I can somewhat understand this because there is something tragically human about aspiring to a great deed, even if it’s only rewarded with failure. Still though, I would argue that you don’t want the people investing your money to be failing tragic heroes, yearning for a glorious death. I would argue that you would want them to be realists, to be rational.

To be rational, to me, means far more than an understandable unwillingness to jump out of a perfectly good airplane. After all, the downside of skydiving is a nonzero chance of death. In math terms this means a small chance of negative infinity (death), which after all still yields negative infinity. Multiply any number times zero and you will still get zero. So negative infinity is the downside and the upside? A really cool few seconds? Pass.

Rationality means the steady and predictable application of logic and math toward all investment opportunities. Warren Buffett is right. In the investing world, we need to let the principles of expected value guide our thinking.

The investments you want to make are those that have limited downside (risk) that is more than compensated by greater upside (reward). It is a disciplined exercise in math. The fancy finance word for this is expected value.

This discipline only demands heroism when it leads you into controversial investments, like our investments in bonds today as just one example. You must be fearless in the application of logic and follow wherever it leads you. Our goal was never to be heroic. Our goal was to be rational, to be realists. Let me explain.

Why I Have Never and Will Never Play the Lottery

One of my favorite investing sayings is “the lottery is a tax on those that can’t do math.” Lotteries offer players the chance to risk a small amount in the hopes of winning huge sums of money. For this chance at riches untold, people line up around the block, and drive for hours to put their hard-earned money down in the hopes of winning. But in almost all cases the odds are hopelessly against the players. While the players think only of their potential winnings, they ignore the math of expected value.

In shorthand, impossible odds of winning even a huge number is a losing proposition. The problem is not the number if you win, its huge! The problem is the odds of you winning, which are tiny.

The price of your lottery ticket is your entry price to make a bad bet, one with a negative expected value. Risking your money at bad odds, is a bad idea. Do it long enough and it will ruin you. There are finer points to be made here when it comes to portfolio construction and the quirks of path dependency, popularized by the great thinker Nassim Taleb, but their full exposition will require more time than we have today. Today our main point is that logic – and math – should be your guide when investing.

The Financial Media’s Hype Machine: Bond Apocalypse!!!

Clients who have visited my office in Naples know that I have a TV that hangs on one wall. What they may not know is that I have never once turned it on. Not once. If I ever do turn it on, which is doubtful, I can promise you that I won’t be watching what passes for “financial news” on it.

Financial television, and frankly 95% of most financial publications, are blissfully unburdened by any real insight and wondrously useful for identifying prospective investments – if you take the opposite view of whatever the TV investment pros are deriding, mocking, and questioning. For that function, if for nothing else, we should be thankful for financial television and media.

The 24-hour news cycle demands the constant hyping of some fear. Most recently the hype-mongers are hawking the “bond apocalypse” that clearly awaits those fools ignorant enough to cling stupidly to their positions in bonds. In my professional career, this is the third such cycle of bond directed hate crime. Oddly enough, prior examples tended to appear around the peaks of the most aggressive risk taking in the equity markets, such as in 2000. Will today’s hyper-ventilations be any better timed? History will be the ultimate judge, but I am willing to go with “no” for now.

But this research note is not about guesses about the future – who will be right and who will be wrong – but rather about a framework for decision making under uncertainty. Our framework is to consider both the outcome we expect, and the odds of that outcome occurring, and compare this to the outcome we do not expect and the odds of it occurring. Finally, I believe Taleb would have us consider the impact of our investments on the portfolio at large.

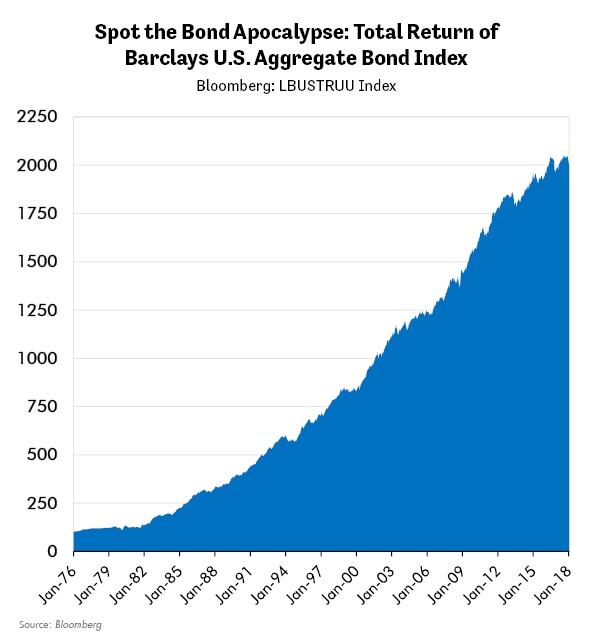

The chart below, the total return of the Barclay’s U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, is one place to start. This broad index includes U.S. Treasury bonds, investment grade corporates, muni bonds, and mortgage backed securities. Shown below, beginning in 1976 it shows a remarkably smooth upward progression for the last generation. Look to the periods of 1994, 2000, and 2013 for prior “bond apocalypses.”

These past “catastrophes” cost investors the staggering declines of 2.9% in 1994, 0.8% in 1999, 2.0% in 2013 and 2.2% year to date. Personally, I find such modest losses – almost all encountered during booming equity markets, as laughable in the context of equity volatility. Equities have seen two 50% crashes in the last 18 years alone. Now THAT is volatility. If armed with this evidence, you are starting to question the proportionality and motives of a strident financial media – good!

In Conclusion

Successful investing is only heroic when the constant demands of reason, realism, and logic lead you to embrace conclusions that are deemed by consensus to be laughable or dangerous. To make these investments, you must have the courage of your conviction - backed by analysis. This is where we find ourselves when we now consider our investment in bonds.

The nature of our disagreements with the market will change in time. What does not change, however, is that we tend to find our best ideas by finding where the passions of financial media run the strongest – and then examining the opposite! That is true not because we are “contrarians” but rather because we are seeking to invest in the areas with the greatest upside and most limited downside. This is both a question of the odds of the event and the outcome of the event.

The saying “what ‘everyone’ knows is not worth knowing” is so often true in investing because of the impact such a commonly shared and universally anticipated belief has upon the odds of an event. The more people believe it to be true, the more the market moves – in advance - to incorporate or “price in” that belief. This leads to the market’s frequent habit of “selling on the news,” when a widely anticipated positive event leads to price weakness and selling. Therefore, it is the unexpected moves that are the most profitable, because the market had previously mispriced the odds of that event.

This is what we mean when we say that the market is a humiliation machine. The best profits come from braving its wrath by daring to disagree with it – but only when the math is in your favor. •