Chief Conclusion

Our valuation discipline is at the heart of how we manage portfolios. Why? Because if you pay too much even for a good company, you can “be right” about the future and still lose money. We watched many investors learn this painful lesson the hard way in the 1990s raging bull market. That’s why we are positioned as we are, in a manner we believe is appropriately defensive for this late stage of the current market cycle.

Investing in the public markets is different from all other endeavors in one key aspect. In investing, you always know what might have been. Think about how unique this is. There is no way for you to know how your life would have turned out if you had gone to a different college, had a different major, married a different person, started your career at a different job, or moved to a different city. Not so in investing! Every day you can examine your past actions with perfect clarity.

All the investors that I respect, that have distinguished themselves in the markets over the decades, know their strengths and weaknesses. This is what Warren Buffett calls their “circle of competence.” Like a patient hitter at the plate in baseball, they wait for their pitches.

That’s why I devote these few pages every couple of weeks to explaining the importance of our investing process and why we take only the risks that we get paid to take. I believe this also means that only rarely do many of the “investments” favored by the world’s twenty-six-year olds show up in our portfolios.

Fearless Twenty-Six-Year Olds During the Internet Bubble

At Wharton I got to know a long list of fellow students who would go on to be leaders in the global investment research community who now work at some of the world’s biggest and most respected investment shops. I am proud of our association then and keep in touch with many of them.

There is one memory, however, I have of some of them that I can never shake: watching them hunched over their screens in the computer labs at Vance Hall, attempting to day-trade their way to glory at the peak of the Internet Bubble. You know who you are! I understood the compulsion but never tried it myself.

It wasn’t just fearless twenty-six-year-old MBA students who tried to live the internet dream. Many investment professionals, charged with the management of real peoples’ savings, tried it too. And for a while, it worked. I can recall very clearly the December 1999 third and final round interview I had in Denver with a company famous at the time for its high-octane growth investing. Over a lunch of catered-in Italian subs, I sat in on their portfolio discussion. One portfolio manager in particular had crushed all his competitors. I still remember the question the director of research asked him: after such a great run, why not go to cash? The portfolio manager answered no. He was another of Jim Roger’s fearless twenty-six-year-olds. I forget how much that portfolio fell from peak to trough, although I remember it was a catastrophic loss. I tried to find its performance last night on my Bloomberg and couldn’t. Maybe it was quietly buried in the performance graveyard where the track records of fearless twenty-six-year olds go to die when the bull market ends.

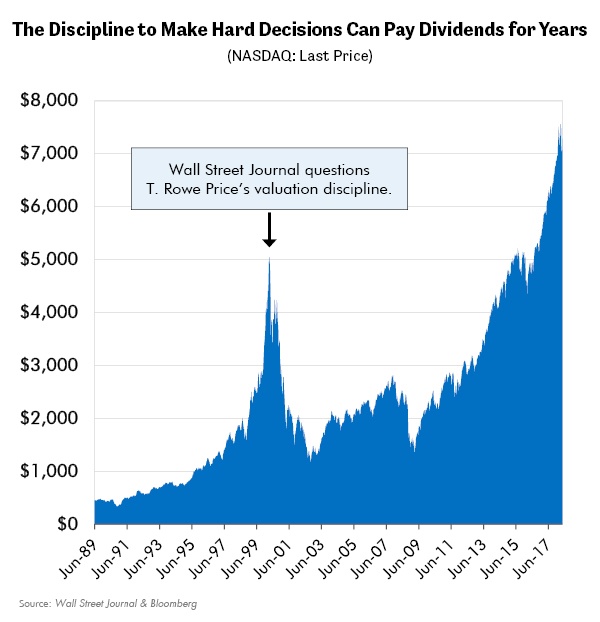

The Wall Street Journal Heckles T. Rowe for its Valuation Discipline Just Days before the Nasdaq Peaked and Began its 80% Decline

This is a funny story. One day at Wharton, what do I read on the front page of the “Money & Investing” section of the much-esteemed Wall Street Journal (WSJ) but the headline “T. Rowe pays High Price for Avoiding Tech Craze.” Google it if you don’t believe me, to witness the marvel of the WSJ deriding a disciplined investment firm just days before the peak of the tech-heavy Nasdaq in one of the biggest bubbles in the history of the world. You can’t make this stuff up.

I was still recuperating from what had been an arduous multi-year journey to land a job at a premier investment research shop. Remember, I was the guy who finalized my application for Wharton’s MBA program in Bangkok, Thailand, in July of 1997, ground zero of what would come to be known as the Asian Crisis. I still remember the day vividly. Arriving in Bangkok, jetlagged beyond all recompense, I watched Bob Pisani at 2am Bangkok time, pace the eerily quiet trading floor of the NYSE, shut down because the circuit breakers had tripped from the huge market plunge. For years I had feared that I was making my move into investment management too late in the cycle. Thankfully I had made it in under the wire. Barely.

So, it was with equanimity that I read that day’s Wall Street Journal and then returned the call of the Director of Research at T. Rowe Price, my future employer. We had already mutually agreed that my employment would commence in the fall of 2000 after my graduation. His awkwardness on the call was apparent. He asked me if I had read the article that day in the Wall Street Journal about the fuddy-duddies at T. Rowe who had the temerity to resist the unstoppable onslaught of the dangerous valuations that attended literally the last few days of the Internet Bubble.

Little did he know that I was non-plussed by the article. Since 1998 I had been the voice of caution among my peers at Wharton, especially those whose day-trading success made them embrace the boundless opportunity of this new era. Their success may have been in retrospect short-lived, and the eventual losses appalling, but for a while it was real money. Their profits were real, for a while anyway. Such positive reinforcement is the fuel for fearless twenty-six-year olds.

But during this call a pleasant surprise awaited me. As part of this awkward semi-apology, T. Rowe was offering to increase my starting compensation by 10%! “Call me anytime.” I said. I meant it. Looking back now, I can understand why the thoughtful folks there were concerned. It’s not every day that the Wall Street Journal questions the investment acumen of a storied investment institution. But T. Rowe was right, the Journal was wrong, and T. Rowe’s clients benefited from the company’s valuation discipline.

The Price – and Reward – of Discipline

The performance of many of T. Rowe’s fund managers had lagged into the peak of the white-hot internet boom. In fact, from December 31, 1997, to February 29, 2000, while the S&P 500 leapt 41 percent, fully 16 of T. Rowe’s 22 actively managed U.S. stock funds underperformed their peers. But from March 23, 2000 to September 20, 2001, while the S&P 500 crashed 36 percent - 21 of T. Rowe’s 23 domestic stock funds beat their Lipper competitors. Furthermore, nine of those 23 funds ranked in the top 10 percent of their categories. Why the huge change in performance? The market environment changed from rabid risk seeking to a more troubled time when discipline was rewarded as the market fell. Many of the investing world’s fearless twenty-six-year olds didn’t make the transition safely. Neither did their clients’ wealth.

When Investors Lose Their Discipline, It Is the Clients Who Pay the Price

You can understand how the decent, hard-working folks at T. Rowe were embarrassed to have that Holy of Holies, the Wall Street Journal, publicly question their judgement and their results. But, to be fair, T. Rowe’s performance had lagged. The problem was that the Wall Street Journal did not understand why, and that the same discipline it ridiculed was about to pay off in spades for T. Rowe’s clients.

The chart below illustrates the market action I just described. I have come to expect similar occurrences and realize they are a natural part of the cycle of boom and bust.

Of course, two decades later, T. Rowe’s assets under management have grown almost four times to more than a trillion dollars. Only in retrospect, when boom had turned to bust, were investors able to judge that the company’s valuation discipline was sound. It took courage for T. Rowe to resist the temptation to give in as so many others did. This courage is what separates a true fiduciary, one that really cares for its clients, from that of a “money manager,” charging fees to manage assets.

Badly shrunken or simply gone were many of T. Rowe’s competitors, the former high fliers of the day. Their own actions removed them from the competition because, in a moment of weakness, they allowed their investments to be directed by fearless twenty-six-year olds.

In Conclusion

We strive to always stay focused on the long term. That is where we believe investors' hopes and dreams are – and that is where our plans are too.

As entrepreneurs, we own our business and will not risk the hard-won efforts that it took to create one of the fastest growing investment advisors in the country. We can only be successful if you are. I wanted you, our clients and friends, to know how we came to think as we do, so that you can understand why we are positioned defensively at this late date in the current market cycle. •