Chief Conclusion

Prolonged market rallies act as a reinforcing mechanism to investors reaching for that extra yield without pausing to consider the risk associated with their actions. By no means is this a new phenomenon, rather it has appeared and reappeared many times throughout history albeit in various forms. We were reminded of this recently when we came across an opportunity to invest money into a virtual community classified as a blockchain opportunity. Suffice to say the community does not exist but alas with your investment, it will! This reminded me of the Fabulous Kingdom of Poyais. A fake land that offered incredible yields relative to domestic London rates at the time in 1825. More on this later.

Over the past few years we have seen with more frequency examples of investors reaching for yield in many different risky assets. In fact, some of those assets do not exist yet people are interested and sadly have taken the plunge. These signs are worrisome for us and our clients. Timing dramatic rises and falls in the market is impossible, so our course of action has been to slowly position into a far more defensive position. With the recent rapid deterioration in credit quality, we think this positioning is prudent and justified.

In just the last few days I came across an “investment” idea in the “blockchain space.” I found it profoundly disturbing for what it said about this current market’s appetite for risk taking. Basically, the idea was to take real money and use it to purchase an interest in a virtual community - one that doesn’t exist. In other words, “fake land.” Soon, its sponsors hope it will turn into a lush and fabulous kingdom, filled with other real people investing their real money in other plots of fake land. Somehow wrapping this hideous idea in “crypto-currencies” and “blockchain” made this a passable idea to those who invested.

I think my mind stopped on this because I have heard it before – in a different way. This pitch is not new but rather an echo of the “Poyais scam” that figured so notoriously in the Panic of 1825 that took place in England. That scheme, which emerged two years before the ultimate peak and subsequent 65% crash in the English stock market, is still notorious for speculative mania nearly two centuries after it happened. I thought this was important to highlight because it is a small, but noteworthy, sign of the times. Investors would have been wise to heed its warning then. I think we should heed it now.

The Fabulous Kingdom of Poyais

The artist rendering above is of the literally fabulous Kingdom of Poyais. Gregor MacGregor, an adventurer and one of history’s greatest scam artists (image below), was able to capture the imagination of the London market and borrow millions (a lot of money two hundred years ago!) on behalf of a non-existent kingdom! ]

How in the world could it be that investors would be so incredibly gullible that they loaned real money to a fake country? What were people thinking? This is the short story of how that came to be.

How in the world could it be that investors would be so incredibly gullible that they loaned real money to a fake country? What were people thinking? This is the short story of how that came to be.

It all started with low interest rates.

English interest rates were falling. English savers were desperate to earn more. They chose to lend money to a new class of “emerging markets” in Latin America that paid 6-8% interest, far more than the 2-3% investors could earn owning solid but unexciting English bonds. Like most booms, this started off looking like a good idea. Bonds for Peru, Colombia and Argentina were offered and, for a while, did fine. Along came MacGregor, the self-styled Grand Cazique of Poyais, with a similar offering. But his country didn’t exist. Eventually this would be a problem. But not yet! In 1822, yield hungry investors snapped up bonds backed by his “fake land”. For a while, everything went great.

His Highness even persuaded seven ships full of people to travel to his promised land of Poyais and colonize its non-existent capital St. Joseph. Hopeful settlers found only unsettled jungle and wilderness. The first boat’s captain, realizing that they had all been duped, sailed away and abandoned the settlers. Most of the stranded settlers died including many children. Eventually, a small minority found their way back to England and reported on MacGregor’s scam.

In 1825, the Bank of England, their central bank and equivalent of the U.S Federal Reserve, reduced the liquidity it provided to the market by “contracting its issue.” If this sounds familiar, it should, because this is underway now in the U.S. in the form of the Fed’s “quantitative tightening.” The lowest quality bonds of even the real countries did poorly. Much of the selling was indiscriminate. The Poyais bonds of course defaulted, causing total loss to the gullible investors.

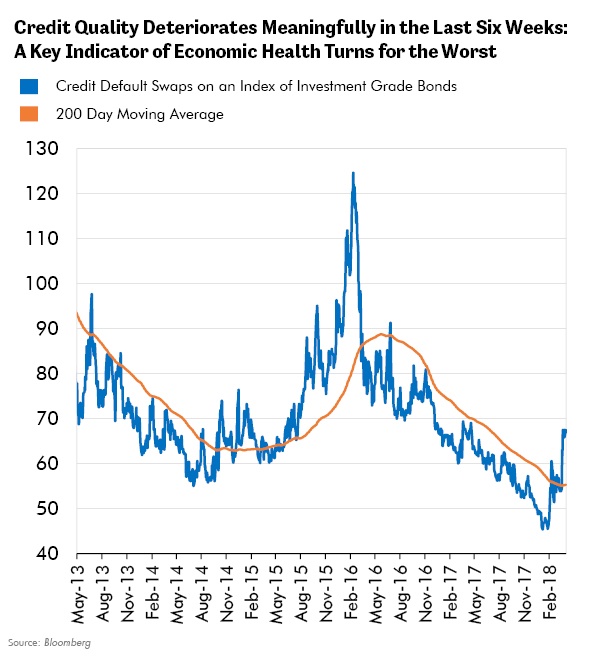

Recent Events: Credit Quality Deteriorates Meaningfully in the U.S.

Credit default swaps (CDS), one of our most trusted leading indicators, have taken a decided turn for the worse, as the chart below displays.

In recent days, CDS have vaulted nearly 50%, reflecting a much higher cost required to hedge against default in a diversified index of investment grade bonds. Credit is the lifeblood of the economy, so any problems in this market much be closely watched.

Its message is clear: that distrust has re-entered our economy. Remember that the Latin root of the word credit, credo, means “I believe.” Fewer investors believe now. This does not necessarily mean that trouble is around the corner. It does mean, however, that trouble is back in the neighborhood. This is an important change from the environment of the last two years of constant improvement in the credit markets. We are paying attention to it and are taking the steps that we believe are prudent to adjust to this new reality, all of which result in making our portfolios more defensive.

We have stated many times that our more defensive positioning would mean that our performance would lag in comparison to that of the market into the peak of a white-hot boom. That is exactly what happened in 2017. Perhaps, in 2018, as credit quality weakens materially, and volatility re-enters the financial vocabulary, our more conservatively positioned portfolio can display its more defensive merits. But we know, as should you, that if you don’t want to look like the market on the way down, you can’t look like the market on the way up.

Our study of history suggests that defensive positioning pays off while credit quality is worsening, as it is clearly doing now. In advance of this deterioration, our portfolios have already been conservatively positioned in four ways: 1.) a higher investment in less cyclical consumer staple companies, 2.) a lower percentage in more cyclical and credit sensitive financial companies – such as banks, 3.) more modest participation than many in the mega-cap high technology leadership of this market that has become increasingly expensive, and 4.) a bond portfolio that is higher in credit quality and thus more defensive than “the market.” All of this we believe is appropriate for where we are in the cycle, now the second longest post-war expansion on record. With the recent deterioration in credit quality we chose to make another incremental step in this direction, only the most recent of many that we have already taken, to sell fully valued equities and add to our holdings of the highest quality bonds. With these incremental changes, we may end up being early, and leave money on the table. But our promise to you is that we will make the changes we think are appropriate, when we think they are appropriate, treating our clients’ money as if it were our own.

Beware the Impact of Emotion on Markets and on Your Decision Making

History has taught me many things. One of the most important is how fickle human nature and emotion are. I study historic extremes of emotion – booms and crashes – because I want to make better decisions today.

There is a timeless pattern to many booms I have both studied and traded, which is that the longer they last, the longer people think they will last. This leads people to be too conservative at the bottom, when the boom is just starting, and too aggressive at the top. Wouldn’t investors be better served to do the opposite? To take more risk early in the cycle when valuations are low – and to take less risk late in the cycle when valuations are high? This is easy to say but hard to do for many; it is very tough to do emotionally.

But the warning from Ecclesiastes in the quote section above should be a caution to us all about how hard timing can be. The future surprises all of us. No one knows the future. For proof look no further than the December 1996 “irrational exuberance” warning from none other than the “maestro” himself Alan Greenspan. His warning proved to be three years too soon! But does our lack of perfect vision into the future mean that we never adjust? Do we just “set it and forget it?” I think the answer must be no.

What makes the most sense is to make a series of smaller course corrections when we are sufficiently deep into a cycle, such as we are now, when we believe that valuations are full and the risks of overstaying our welcome are high. Let me be very clear: we are not trying to “time the market.” No one can do that. We are, however, managing risk.

If you look hard for it, you can see risk. You see it in valuations – in the price investors are willing to pay for some of the most popular investments. You see it in sentiment, such as who in their right mind could invest real money in fake land. And – even worse than the Poyais Scam of 1822 – today’s project’s promoter readily admits that its fake! What should reasonable people do about this?

This becomes a problem even for conservatively positioned investors, because illogical investors can create problems for us too. If investors en masse will not think critically about what they are buying, do you really think they will think critically about what they are selling? Can you really think for a moment that values will stop at “fair value?” Sadly, I fear the answer is no. When emotion reverses from greed to fear the result you so often see is expensive markets becoming incredibly cheap. Those are the opportunities when we want to follow Mr. Buffett’s advice and be greedy when others are fearful.

But if we are to have any hope of executing upon this goal, we must first be willing to follow the counsel of Bernard Baruch and “sell too soon,” by moving out of fully valued investments and moving into safer or more undervalued assets.

In Conclusion

We have no crystal ball on when this boom, as many before it, will turn to bust. Just look at the cautionary tales we have examined in just a few pages. Even the mighty Alan Greenspan was three years early. Rather than shrug and give up, in the face of difficulty however, I believe that we owe it to our clients to take measured steps to make the portfolio safer when we think its justified. This is one of those times. There will be more such times in the future.

The steps we have taken over the past few years have all been incremental steps in the same direction of owning more higher quality bonds and equities that we believe have defensive characteristics. Our goal in doing so is to mitigate the downside and avoid the anguished fate of the buyers’ remorse in Thomas Peacock’s “Chorus of the Bubble Buyers” shown below, about the Crash of 1825.

Oh! Where are the hopes we have met in a morning…

When we laughed at the croakers that bade us take warning,

Who once were our scorn and now make us their sport.

…Now curst be the projects, and curst the projectors,

And curst be the bubbles before us that rolled,

Which, bursting, have left us like desolate spectres,

…Grim phantoms of wrath that shall never be laid.”•

Sources:

"Sketch of the Mosquito Shore": https://archive.org/details/sketchmosquitos00conggoog

Gregor MacGregor: Wikipedia