Chief Conclusion

Today’s “Trends and Tail Risks” is about what happens to leadership stocks when confidence flees, and bull markets turn into bear markets, which has taken place on average every nine and a half years over the last two hundred years. We are now nine and one quarter years into the current upcycle.

I believe that discipline is one of the most valuable attributes of successful investors; those who have learned to overcome emotion and base instincts that, left alone, could conspire against investment success. This is a foundational tenet of behavioral finance, which is the study of common psychological fallacies.

Our own very human psychological shortcomings are even shared by our closest relatives in the animal kingdom, the monkeys. The best example of this at work is the famous “monkey trap,” which can be seen in the short video here.

(Spoiler alert – the monkey is later released unharmed, despite its obvious displeasure at being captured.)

Everything That Has a Beginning, Has an End.

One path to outperformance is to own a full helping of the stocks that will be the cycle’s leaders early in an upcycle. Stocks in leadership sectors often have a lot more helping them succeed than simply improving fundamentals. An equally powerful, and sometimes more impactful, driver comes from rising investor confidence. This confidence can express itself in an expanding valuation multiple which the market is willing to pay for a company’s improving fundamentals. Let’s take a quick illustrative look at Netflix (NFLX), for instance, one of the “FAANGs” (Facebook, Amazon.com, Apple, Netflix, and Google) dominating this market cycle.

Netflix’s share price is up an amazing 100-fold since 2008. Netflix’s revenues are up about 10x since 2008. So, it’s a reasonable approximation to ascribe 10x of the stock’s appreciation since then to improving fundamentals, with revenue as a rough proxy for “fundamentals.” However, the stock’s multiple to revenues has also expanded 10x, rising from 1x its 2008 revenues to about 10x its expected revenues for 2018. Many people fail to realize that half of the stock’s return has not come from fundamental improvement but rather from an expanding multiple, which I believe is simply from rising confidence.

These twin drivers are multiplicative: 10x from fundamental improvement and 10x from higher valuation thanks to rising investor confidence. Tenfold times tenfold is 100-fold, the gain in the stock since 2008. So, it’s not an exaggeration to say that half of Netflix’s outperformance is due to rising confidence. If the stock’s valuation were to fall back to 2008 levels on unchanged fundamentals, it would power a 90% decline in the share price. Ouch!

In the scenario I outline above, to even start to make a dent in that 90% valuation driven decline, the company’s fundamentals would have to keep improving. That’s why I believe so many investors imperil their late-cycle gains by ignoring valuation. History suggests that there can be a horrible cost for those investors who ignore valuation and cling too tight-fistedly to the cycle’s winners. The monkey trap awaits them.

Will Past Be Prologue? Market Leaders Can Fall More Than 75% or More from Their Peaks.

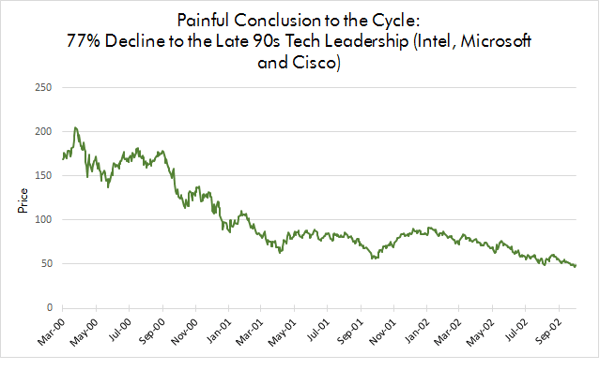

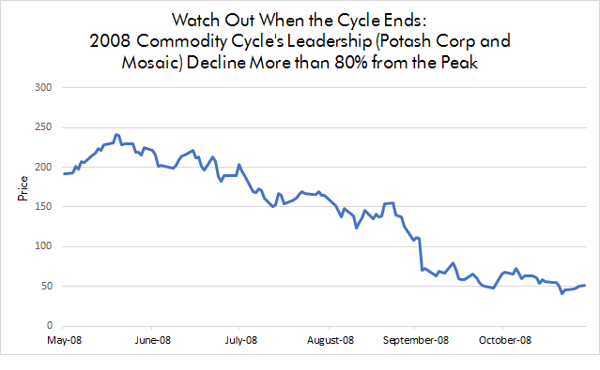

In my career I have seen the aftermath of two very different cycles, the late 1990s tech boom and bust and the meteoric rise and fateful crash of the 2003-2008 commodity cycle. In both instances when the cycle was over, the former leadership groups crashed more than 75%, a far worse decline than the still-painful 50% drop in the S&P 500 index. The charts below show the extent of the damage. The sky-high valuations killed these stocks when the cycle turned. I believe that’s why they declined far more than the market. And these declines took place in stocks that were financially sound, true industry leaders - not speculative ventures.

The way you lose 75% is that you get cut in half once (down 50%) and then cut in half again (another 50% from there). Down 50% means that your investment must double to break even. Down 75% and your investment must quadruple to break even. Such losses can be devastating. I believe the underappreciated culprit behind these epic end of cycle collapses was that the extended valuations made them vulnerable.

In Conclusion

Of course, no one has a crystal ball to tell them the day at which any stock will peak. The market does, however, have a depressingly predictable business cycle length which averages nine and a half years. In just eight weeks, our current cycle will be that average age. The last two downcycles took the broader market down 50%. The former leaders were crushed even worse than that for another 50%, to end up down 75% or more. Those losses are hard to recoup.

Our philosophy is to be proactive. Our goal is to avoid the monkey trap. This means that we won’t hesitate to use the valuation tools that we believe have served us well for years. This means we reduce substantially or eliminate our fully valued winners, especially as we get deeper into the cycle. This is the thinking behind the changes we consider to make our portfolios more defensive, particularly a reduced exposure to the “hot” tech sector, our investments in stable growth companies, and our growing US treasury bond holdings.

The price that we are likely to pay for this valuation discipline, and certainly we have paid this cycle, is to leave money on the table by “selling too soon.” We do so willingly because this is not our first rodeo. We have seen the damage overstaying your welcome can cause, particularly the carnage suffered by the former leadership of a dying cycle. I believe that valuation discipline, and a willingness to sell early, are the best tools we have to avoid the monkey trap. •