CHIEF CONCLUSION

"History doesn’t repeat but it does rhyme." - Mark Twain

Financial markets look ahead. Wait for the news and you may fall behind the biggest moves. It appears we are now very deep into one of the longest cycles of post-World War II financial history. Markets are seemingly falling “for no reason.” Is such a cyclical turn underway now? We continue to believe that more defensive portfolios are called for in this aging cycle. Today we review the lessons of prior cycles to study what may lie ahead.

"When you feel like bragging, its probably time to sell." - John Neff

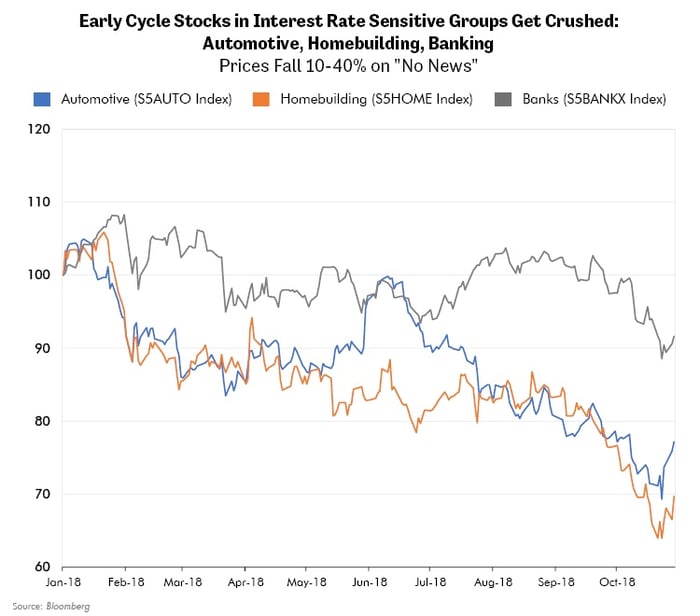

The stocks of some of the most interest rate sensitive investments in the U.S. have fallen dramatically, on little news. Below we show the performance of such sectors in 2018. We highlight them because historic trading patterns suggest that they are among the most sensitive to higher interest rates: autos, housing, and banks.

As the chart above demonstrates, these sectors have fallen quite hard, especially autos and housing, and have done so on relatively no ill news. Their violent down moves recall the last downcycle, when despite rising earnings forecasts, these interest rate sensitive sectors began declining way back in 2005, a full two years ahead of the ultimate peak of the market. Then, their decline – while troubling for shareholders – held no dire warning for the broader markets. Two full years of rallying awaited the cycle’s end.

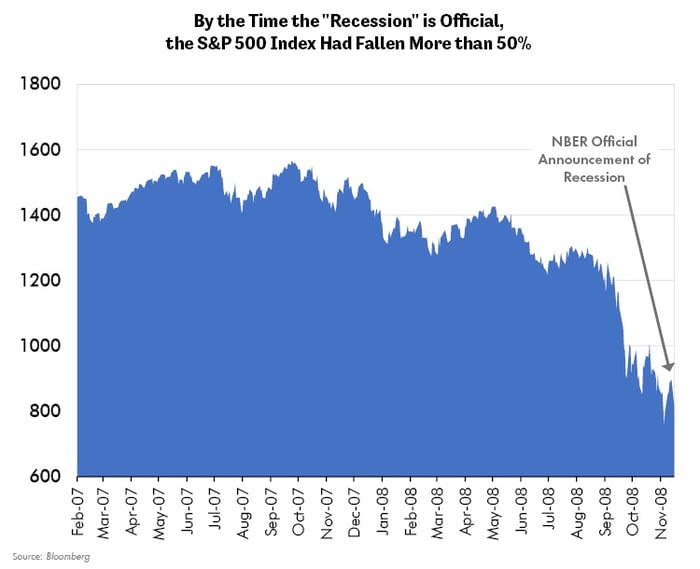

So, timing cycles is hard. Pity the poor folks at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER.org). Theirs is the thankless task to name and date the economic cycle. I remember quite clearly the day, nearly a decade ago, when in December of 2008 the NBER announced that the U.S. economy had been in a recession for a full year. While this was important “news” it did investors no good. The stock market had already fallen 50% by then, as the chart below displays. The news in the black days of December 2008 was awful. Stocks already reflected that.

The takeaway? Financial markets are generally forward looking, sometimes amazingly so. You will likely only lay up disappointment for yourself if you think that you can wait for “news” to make up your mind. More often than not, by the time you get the “news,” prices have already moved. In our experience, the financial markets demand that you be early, if successful investing is your goal. The good news is, you can study history to learn from prior cycles.

“It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you might be swept off to.” – J. R. R. Tolkien

Don’t be too hard on the NBER. Cycles are tricky, tripping up even the best and brightest. Let me illustrate with a story from a prior cycle, the 2000 peak.

Many years ago, when the Earth was young, I was an aspiring MBA student earning my degree in Finance at Wharton, scheduled to graduate in May of 2000. To those of you who were active in the markets back then, you may recall that the great Internet Boom was just about to turn into a bust. The cycle had already peaked, in fact. In May of 2000, however, there was little “news” of such impending disaster.

The stock market was near all-time highs. Unemployment was low. Almost everyone appeared bullish. In fact, so deeply held was the conviction among many that “this time was different” that a rumored 30 or so of my approximately 750 fellow aspiring Wharton grads dropped out before graduating to found their own internet companies! Talk about bullishness! That memory I can never forget.

Of course, that time was not “different.” The wonderfully bullish headlines of the day would, in the coming months, yield to disappointment and recession, and another 50% drop in the U.S. stock market.

While current news may not be able to help us with the future direction of the stock market, that does not mean that we are bereft of useful indicators. In fact, we have spent our careers seeking these out in our long study of cycles. Below, we examine again the “yield curve;” which I believe is one of the most useful financial markets indicators that we have come across.

The sun also rises, and the sun goes down,

And hastens to the place where it arose.

The wind goes toward the south,

And turns around to the north;

The wind whirls about continually,

And comes again on its circuit.

All the rivers run into the sea,

Yet the sea is not full;

To the place from which the rivers come,

There they return again.

-Ecclesiastes 1:5-7

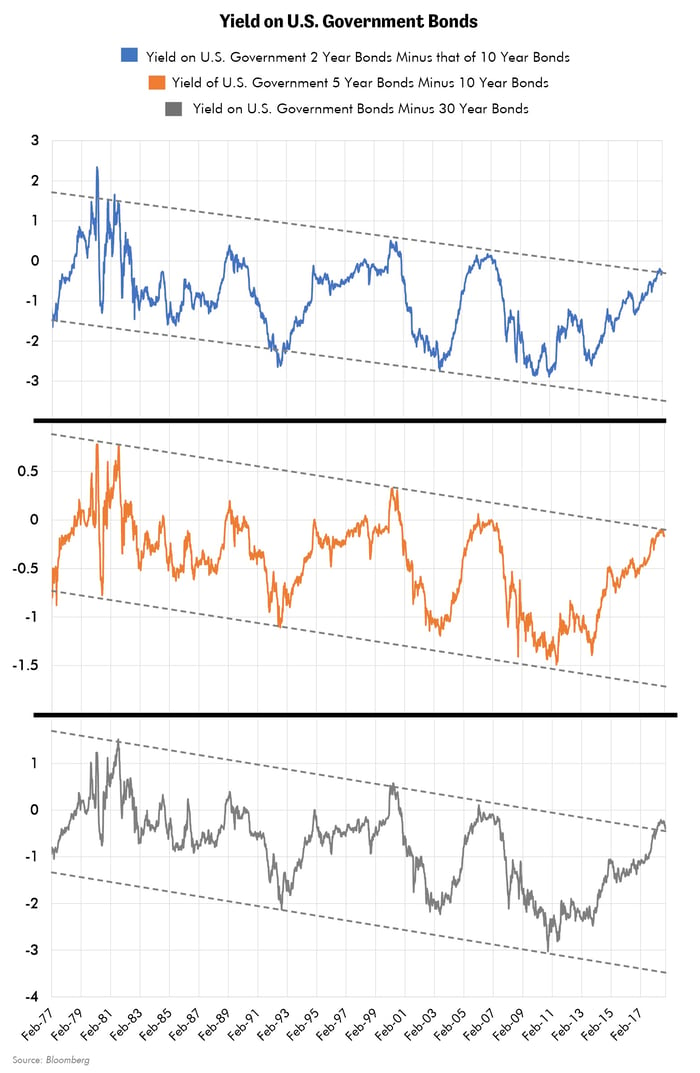

Cycles have a long history. What comes around, goes around. In our experience, one of the most reliable indicators has proven to be the yield curve. The yield cure is a fancy term for the differences in interest rates among bonds of different maturities. Below we show the U.S. government bond yield curves for many important tenors, such as the 2 to 10s, 5 to 10s, and 5 year versus 30 year.

There are two trends that jump out. First, the declining trend of lower lows and lower highs, which I believe is driven by the imperative of falling rates necessary to “stimulate” our over-indebted economy. Second, we are now challenging the upward limit of that downtrend. Will the past be prologue? If so, then we may be witnessing the first days of an important turn in the cycle.

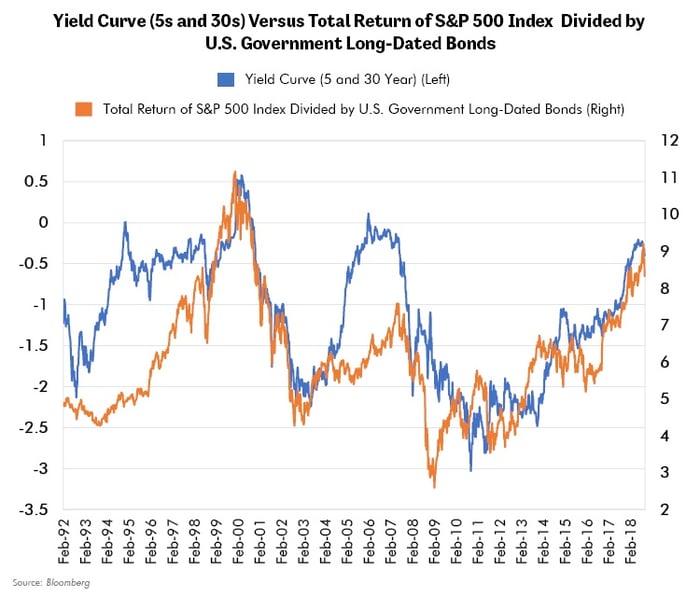

In prior research we have covered this topic, in January of 2017 in “The Message of the Yield Curve” and again in June of 2018 in “Inconceivable.” Interest rates represent the price to rent money, likely the world’s most important commodity. The yield curves above, showing the price to rent money for different periods, have a history of being one of the first financial indicators to reliably inflect ahead of or during important cyclical turns. Sometimes, such as during the 2000 cycle, the curve’s “inversion” and move downward coincided with the peak of the U.S. equity market. Other times, such as in the cycle that ended in 2008, the curve’s downward move came nearly a full year ahead of the ultimate peak in equities. So even a tool that appears as reliable as the yield curve is open to interpretation. How then, can we work to thoughtfully invest portfolios this late into an aging cycle – especially given the burden of not waiting for “news?” The answer is that we must be prepared to move early, ahead of the news, to build defensiveness into our investments. We do so not because we have a crystal ball to see the future, but rather because we lack such perfect vision.

Everything that has a beginning, has an end. – The Matrix

To invest your money in the financial markets is to place it at risk. People take this risk because they want their money to grow. Otherwise, they would just bury it in their backyard.

Once investors decide to place that money at risk in the markets, the job of our analytical team, if done well, is to distinguish good risks from bad risks. Bad risks, to us, are risks that our research team believes do not adequately compensate for investing in them. The deeper we get into a market cycle – and the more closely we approach the peak – the harder it becomes to identify such opportunities. During such times, our investments – and thus our performance – will be different from those of “the market.” Driving us, at those times, is the knowledge – hard fought – that markets move ahead of the news.

Our goal is to not be a victim of the cycle, rather to profit from its volatility. This goal, frankly, takes a lot of courage to not look like the market in the waning days of the boom. What guides us is our valuation discipline to only take the risks for which we think we should be paid to take.

We cannot see the future with perfect clarity. This means that we will never be able to control the returns that we earn. What we can do, however, is try to control the risks we take. Returns are something that happen later, after you take the risk. This discipline may demand that we hold more defensive investments, watching from the sidelines as the euphoria rages on during a time that may so often accompany the terminal and most dangerous part of the cycle. Our two chief strategies in doing so, are increasing our holdings of U.S. government treasury bonds and making our equity investments more conservative.

We have traded literally hundreds of cycles across many industries, financial markets, and countries. Our goal is to use this knowledge to better manage the volatility of cycles. Our goal is to invest more aggressively early in the cycle, when we get well-paid to take risks, and more conservatively later in the cycle, when downside risks begin to pile up. This discipline, and our willingness to move ahead of the news, is an important part of our research process. The message of the yield curve is one important tool that can help fine tune our portfolio construction as the days of the cycle grow long.