CHIEF CONCLUSION

Whoever said “its who you know that counts” was definitely speaking about the investment business. In a confusing world, drowning in data, how to make sense of it all and plot an intelligent way forward? It’s not easy. That’s for sure. Today we walk through our experience with one trusted market observer and outline why his unique framework is so valuable to us and how its influencing how our research team thinks about the future.

One of the best things about being in the markets for the past two decades is meeting smart people. In fact, you might go so far as to say that 95% of investing is to know who to listen to, and who to ignore. My long-time friend and experienced market commentator, Barry Bannister, currently the chief strategist at Stifel, is one of those you want to listen to.

I first met Barry way back in 2002 when I was a young equity analyst at T. Rowe Price. My Wharton MBA was still shiny, and I was scouring the world for opportunity. Little did I know how helpful the assistance from my future friend Barry would be. Barry was a sell-side analyst at Legg Mason specializing in the industrial sector. From the start, I could tell that there was something different about the way Barry thought.

What I loved about Barry then, and what I still love about him now, is how he thinks: very long term and in terms of cycles. Performance often lurches from one extreme to the next typically when no one is expecting it. So, you really must be wired differently to think in terms of cycles and how much things can change. Barry had just written a piece in April of 2002 on the prospect for a multi-year bull market in commodities – of all things. Commodities were enduring one of the deepest and longest bear markets ever, so I was intrigued by how different his thinking was. I was already independently noodling around the same concept, so I studied his thinking with great interest.

His research, among many important points, highlighted one key fact, namely that the markets were coming off an historically extreme level of stock market overvaluation and - at the same time - commodity undervaluation. Two extremes at the same time in the opposite direction. That was interesting. Prior such episodes were rare and had typically resulted in the reversal of the prior period’s trends. This suggested a future of lackluster equity performance while, at the same time, strong commodity outperformance. Of course, Barry nailed that cycle – which was the dominant investment theme of the decade - in a way that few did. Barry was right for the right reasons, which is so much more valuable than just being “right. “That’s the kind of thing you love to see to inspire confidence.

Déjà vu all over again?

Accordingly, it was with great interest that I read a note on September 15, 2020 from Barry outlining that – once more – the markets were approaching such historic extremes again. Years of equity outperformance and commodity underperformance were giving me déjà vu all over again. Now let me be very clear: no one knows for sure when extremes will reverse. Frankly, sometimes they have a pesky habit of enduring for longer and going to greater extremes than anyone expects. So, today I am not calling a turn or making a prediction. I am however, paying attention. And you should too.

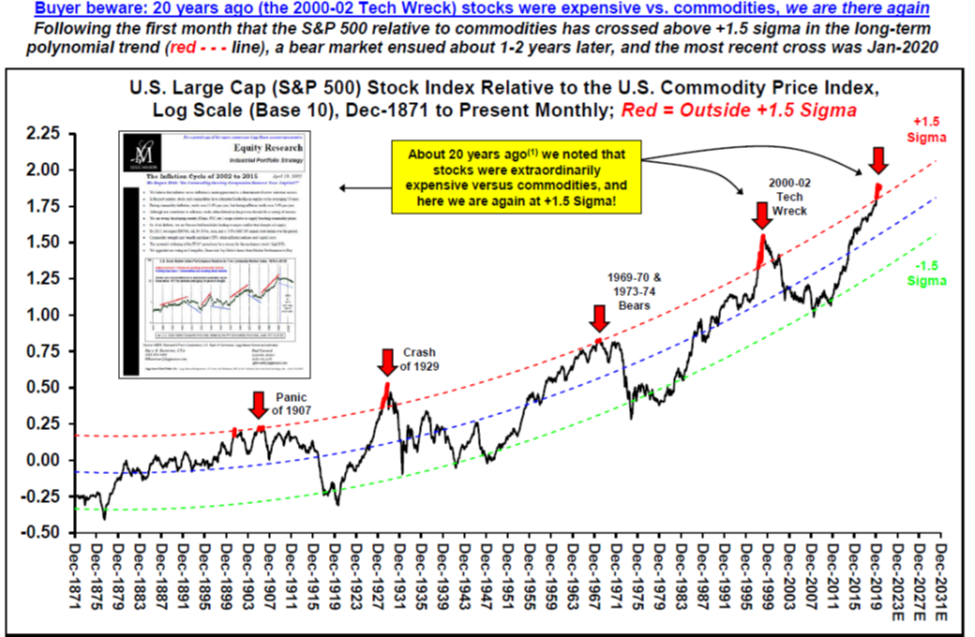

Source: Barry Bannister, Note, 9/15/20

The chart above is from Barry’s recent note and shows the ratio of performance of large capitalization U.S. equities versus the commodity price index. The chart clearly shows what extreme levels with which the markets are now flirting. This bears watching, particularly because gold, the best leading indicator of commodities, is now on the move, doubling in the last five years in fact. This suggests that commodities in general may not be long in following gold higher. Is this – maybe(?) – the earliest leading indicator of a future change of market leadership back to commodities and their related equities? Stranger things have happened. We should watch this space carefully.

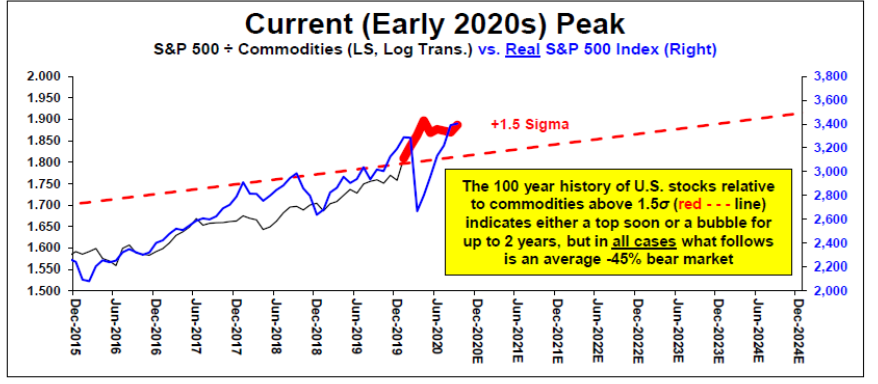

At such extreme levels of over and under valuation, cyclical risks are high. According to Barry’s note, 100 years of data suggests that once the cycle turns, the average peak to trough decline in equities is 45%. Not a small decline. If such a decline began today, that would take the S&P 500 from 3500 to 2000 (see chart below.) That certainly got my attention, although no one can forecast with certainty the eventual timing of any cyclical change.

Source: Barry Bannister, Note, 9/15/20

As risk managers, we worry about such a decline because it would crush the hard-won savings that investors, and especially retirees, are risking in the markets. That is potentially a terrifying problem – for almost everyone – but perhaps not for us. Not if we play our cards right. Let me explain.

Longtime readers will know by now that our philosophy is to “own the solution” that can profit by solving the problem about which we are concerned. Barry’s work quite eloquently shows that the verdict of history is clear on the solution: the strong outperformance of gold and other commodities. Why? Cycles don’t die of old age. Something kills them. What has killed prior equity growth cycles? One answer is a rising cost of living. This has been presaged by higher gold prices and followed soon thereafter by higher commodity prices. This takes down formerly high-flying growth equity driven markets for two reasons. First, a rising cost of living lowers demand and raises companies’ cost of production, which weighs upon earnings. However, the second driver is by far the most damaging: the collapse of formerly sky-high equity valuations.

Declining valuations are indeed the silent killer that is behind all prior secular bear markets in growth equities. Here a look back at the “Nifty 50” growth equity cycle is instructive. A powerful growth stock rally had raged since the “go-go years” of the mid-1960s and peaked in 1972. The price to earnings ratio on the trailing twelve months of earnings for these stocks was a lofty 36x. The high-flying Nasdaq now trades at twice that, at 72x trailing earnings. During the ten years following the Nifty 50 peak, the median valuation of this group fell 66%, which worked to compress equity valuations by almost 10% per year. Now let me be clear, while valuations fell, earnings indeed rose. The net effect of both combined to make a “lost decade” for equities whose returns were flat for the next ten years. Earnings rose but valuations fell! So, stock prices were flat. To me, that result is borderline criminal: to risk your money in the markets for a decade for no return.

In a more recent incarnation of growth equity ebullience, the 1990s Tech Bubble, investors also suffered ten years of no price appreciation in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, thirteen years of the same in the S&P 500, and a crippling seventeen years in the Nasdaq. That’s extraordinary.

We highlight these examples because we believe that the same forces that have historically called an end to the cycle of growth equities may be starting to poke their head up right now: rising gold and commodity prices. Both are rallying now - from a low base. But do not underestimate their potency and power to eventually end our current long cycle of growth equity leadership. Note that key word: eventually. Frankly, I have no idea if such an end game is already underway, starts tomorrow, or starts two years from now. I doubt very seriously that anyone else knows for sure either. Investing is about decision making under uncertainty.

What does this suggest to us is the best investment strategy?

Here is the great paradox of risk management: How to thoughtfully construct a portfolio that is resilient to these risks without unduly underperforming should your insights be early? And how to avoid overstaying a profitable welcome in strongly performing securities that may face a growing danger of a cyclical decline? No one said thoughtful investing would be easy!

Our preferred portfolio construction has been to own stocks with a quality bias that can hold up well even under slow growth. This has been a big help. We also have a meaningful investment in the kinds of securities that we believe would benefit strongly from a resurgence in that which could kill growth stocks: gold and commodities. In fact, commodity linked equities may figure prominently among the ones we favor in the future. We do believe that its prudent to have “one foot out of the door” and have balanced exposure to such investments, rather than what many investors are doing these days, which is to continue to dangerously overweight growth names and hope for the best. Like so many things, that works until it doesn’t.

A Word about The Role of Politics: the Pattern of Populistic Reflation

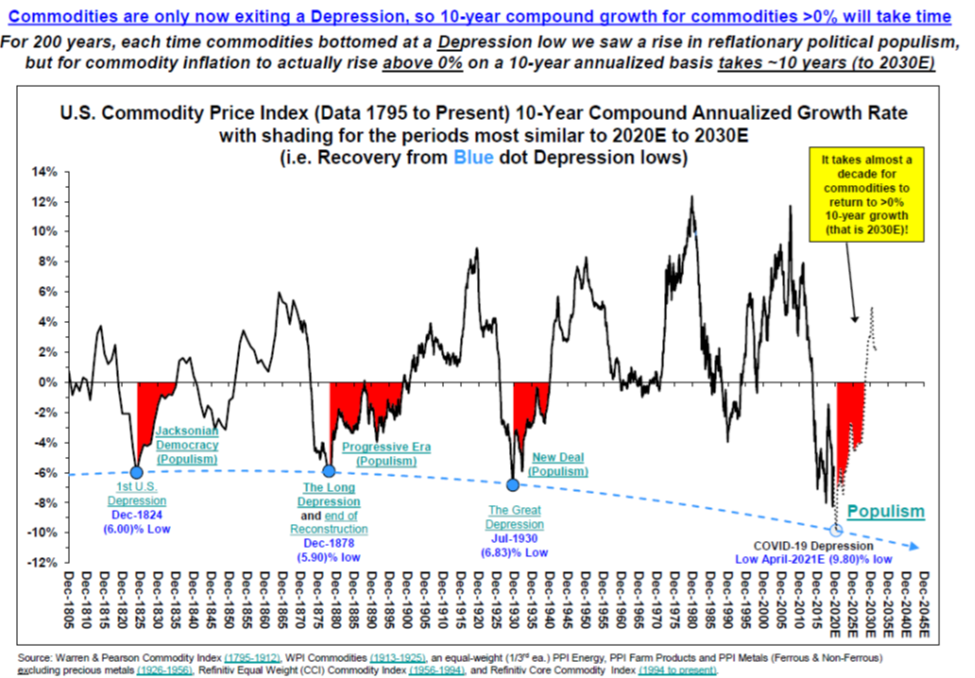

I was intrigued by this last chart of Barry’s, displayed below, because it highlights a point grabbed from today’s headlines: the rise of divisive populist politics. Below in red Barry highlights that extended periods of weak commodity prices have elicited secular political changes, such as the Progressive Era of the 1870s, “New Deal” populism of the 1930s and the vast expansion of the government, and now – one of the deepest multi-year commodity price declines on record.

Source: Barry Bannister, Note, 9/15/20

Certainly, it is lost on few of us how divisive our politics have become. But it’s likely that few have made the deeper connections that Barry has, that weak commodities and slow growth may have a hand in causing this change in our politics.

Are we living through another secular turn, where government expands its mandate exponentially? This marked prior cyclical turns. I have certainly noticed that the Covid-19 crisis has whetted the appetite of many citizens for a bigger role for government. Look no further than forced lock downs, quarantines, mask mandates, and multi-trillion-dollar income subsidies. Once government expands, will this newly grown government ever shrink? Once the momentum of big government is underway, how long must it go on – and must it overshoot before – at some distant date – it begins to recede once more?

In Conclusion

As I have continuously stressed over the years writing this publication, no one including and especially me, has a crystal ball. Believe me, if I did, you’d know about it! Our research team believes that the best path to increasing the probability of getting the future correct is to fervently study the past, especially from a long-term perspective. The study of the past includes understanding how economic cycles work and finding indicators that have been successful at predicting the future. Our research department tries hard to do both. However, our humility requires us to consider that we might be wrong. So, we spend a lot of effort trying to balance our portfolios so that they can perform well through many different and unexpected environments.

Though this is a great challenge to get right, we are thankfully not without tools. One of our secret weapons is the comfort that comes from knowing whose insight to trust. After many years, we count ourselves lucky to have a small handful of trusted observers with whom we have faced uncertain markets. When it comes to investing, we believe that its who you know that counts – especially if you are on the lookout for the next big thing.