Applying the Lessons of the Past to Today’s Market Turmoil

Markets have been very volatile lately with the drumbeat of troubling events increasing in both pace and strength. It’s a reasonable time for investors to soberly consider other times of great volatility, such as the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009. Then, the path to success was very narrow. Successful investors during that time period deeply understood the credit markets, which are far larger and frankly far more important than the equity markets that consume nearly all of the time and attention of CNBC’s talking heads. Understanding the credit markets will likely also be the key to success in this market cycle. This means understanding a few key issues:

- where the initial impetus of credit weakness came from;

- what institutions it impacts;

- how cause and effect will propagate this impact across global markets; and finally,

- the likely ultimate resolution needed to stabilize the market.

I believe that the latest cycle of credit weakness is the causal driver behind the recent expression of stock market turmoil. Furthermore I believe this deeper bout of global credit distress began in China in 2011 as I explain below.

China, during the torrid growth of the last 15 years or so, experienced the world’s biggest credit boom. It makes perfect sense that somewhere along the way the cumulative weight of capital allocation errors would build up during such a period. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that China is down for the count. All investors should reflect on the example of the American credit boom of the 1920s. At its height, investors looked forward confidently to an “American century” and indeed it happened – but only after the U.S. stock market fell 90%, our unemployment rate hit 33%, and we successfully navigated a world war. Never underestimate the market’s sense of irony! Today’s “Trends and Tail Risks” does a deeper dive on China’s credit and currency markets, to examine their central role in this latest bout of market turmoil. My purpose is to understand the genesis of this weakness so that we might understand its end.

Preparation is Key: the Difficulty of Analyzing Rare Financial Events in Real Time

A large part of the success I had navigating the subprime fiasco was because I studied history. Frankly, I always puzzled over why so many other investors failed to do so. To me, it would have been the height of arrogance if I had failed to study and heed these lessons. After all, no championship team would consider its preparation complete for a big game without first meticulously studying the films of its opponents past games. Shouldn’t investors, entrusted with the far more serious task of the care and growth of savings, approach their craft with the same level of professionalism and determination?

The markets that have confronted investors in the last 18 months have been profoundly confusing to many, and – if anything – show signs of becoming even more so. This should come as no surprise to avid readers of this publication. The single most consistent theme I have communicated in these pages has been my belief that this is not a normal market environment. I fear that those who erroneously approach this market as if it were “normal” are storing up grief for themselves. My view is not without controversy. Frankly some degree of controversy, typically the more the better, has been a key component of all my periods of strong outperformance. Perhaps, when the history of events now underway is written, this period will serve as another such example of a profitable disagreement with the market.

The Causality of Credit: Weakness Originates in China in 2011 Before Spreading Further

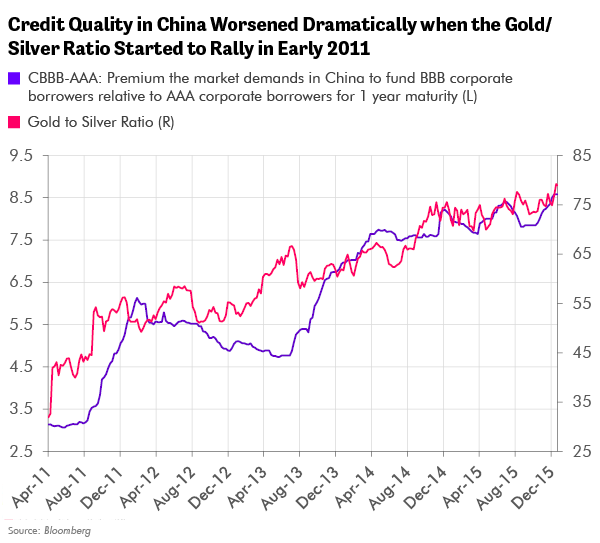

Frequent readers of this publication understand my affinity for using market-driven indicators to gauge where we are in the cycle. The ratio of the gold price to the silver price, the gold/silver ratio, is one of my most trusted indicators. The chart below illustrates that two events happened within rapid succession of each other: the first was a trough in the gold/silver ratio in April of 2011 followed by a worsening in Chinese credit quality in June of 2011.

When the gold price is rallying relative to the price of silver, global liquidity is typically falling. It makes perfect sense to me that as global liquidity peaked and started to fall that the credit markets would show their first signs of weakness. Furthermore, in light of this new trend of deterioration, it also makes perfect sense to me that the market requires close monitoring.

I had the good fortune of traveling to China in March of 2012 to study its credit market, in particular its enormous “shadow banking system,” with some respected colleagues. I saw many signs that were eerily reminiscent of the excesses that helped me to identify early the 2007 peak in the U.S. credit markets. As always, the pace of future events is difficult to foresee. Thankfully, history provides a wealth of examples from which a disciplined student of markets can learn. My concerns about China at that time were not widely shared. Recent events have made the markets much more sensitive to events in China, and for good reason.

I have always believed strongly that the optimal asset allocation for investors changes over time as a function of how the cycle is changing. Accordingly, my thoughts on the most appropriate asset allocation have changed over the last few years, in my attempt to maximize return while minimizing risk. Beginning in 2013 my counsel was to exit emerging markets on fears, now fully justified, that a rising dollar could lead to a self-reinforcing negative cycle in these markets. In early 2014, the commodity and credit markets showed disturbing signs of peaking (“Making Volatility Our Friend: Trading the Kitchin Cycle,” May 28th 2014 and “Is Credit Quality Peaking?” August 6th, 2014). Clearly the scope of investments that seem to offer the safest returns has dwindled over time. In early 2014, longer duration, higher quality bonds offered compelling value given the slowdown I expected, especially given the bruising 2013 through which such bonds had just suffered, the worst market for them since 1978 (“Our Bond Strategy: The Power of Duration.” October 8, 2014).

I held out hope that a rebound in the short-term Kitchin Inventory Cycle would enable a more profitable time for some commodity producers and emerging markets. However, this anticipated short-term cyclical improvement was overwhelmed by the deep intensification of China’s problems, expressing themselves now most glaringly in its dangerously weakening currency (“Interplay of Cycles,” November 18, 2015). Commodity prices are now at levels that should represent solid long-term value, however investors cannot ignore the threat of further short term weakness from China.

Market observers are confronted with many examples of China-driven weakness spilling over more broadly to markets that once were seemingly isolated from such concerns. For instance, look no further than the more than 1,000 point swing in just one day of the Dow Jones Industrial Average back in August. This swoon took place immediately following one of the largest devaluations of the Chinese currency in recent memory. Many markets would recover to hit new highs, but the fault lines in the market were established. After stabilizing through November, China’s currency would weaken to new lows in late December of 2015 and in early January of the new year, throwing global markets into disarray again. The markets are making a clear statement: they are very concerned about events within China, especially those that threaten to devalue its currency. For more than a year now, I have tried to answer the question of how long the U.S. could remain strong while so many other markets faltered ("Uniquely American Outperformance?” December 24, 2014). Below I outline why I think the market is concerned about China and how investors should invest in this environment.

Chinese Currency Devaluation: One of the Biggest Risks Facing the Markets

Since August the Chinese currency has changed trend, from strengthening to weakening. This trend change is creating all kinds of havoc in global markets. Problems that were once seemingly isolated to the beleaguered commodity and emerging markets are now spreading to other markets. I believe the evidence is rising that China’s weakening currency is at the heart of this. Perhaps an illustrative example from the steel markets might help explain why events in China are so important.

The Example of Steel

It was not that long ago, when I was a young analyst at T. Rowe Price, that the rapid growth of China’s steel industry literally transformed the world of steel. Amazingly, for a number of years, China’s annual year on year growth in steel capacity was equal to the entire cumulative capacity of the U.S. steel industry - that took 300 years to construct! Chinese steel capacity is now many, many times that of the U.S., which is troubling news indeed now that China’s steel markets are in oversupply. China is already a formidable competitor in steel, exporting products at prices lower than the cost of production of many U.S. steel mills. More than a year ago I identified the danger this represented to the U.S. steel industry (“Unsustainable Steel Premiums,” September 3, 2014). Since then, high cost U.S. steel equities have fallen close to 90% while steel prices have almost been cut in half.

Cheap steel exports from China were the key global driver of this dramatic decline in the U.S. steel market. Clearly the situation is now grim for U.S. steel producers. Should China’s currency devalue, however, China’s cost of production in dollars would fall even more, putting even more pressure on U.S. – and in fact global – steel prices. Falling Chinese currency values are literally the last thing the world needs right now. The challenge is that a falling currency is the orthodox policy prescription most central bankers would suggest for China to stem the tide of credit distress and deflation within China that I outlined in my first chart. Frankly a strengthening U.S. dollar, supported by the Fed’s decision to launch a tightening cycle, simply puts more pressure on China to devalue its currency, as I outlined more than a year ago (“The Dark Side of China, September 24, 2014). I can see clearly the outline of a potential policy mistake into which our leaders could stumble.

Chinese Currency Changes and Deflation: a Strong Correlation

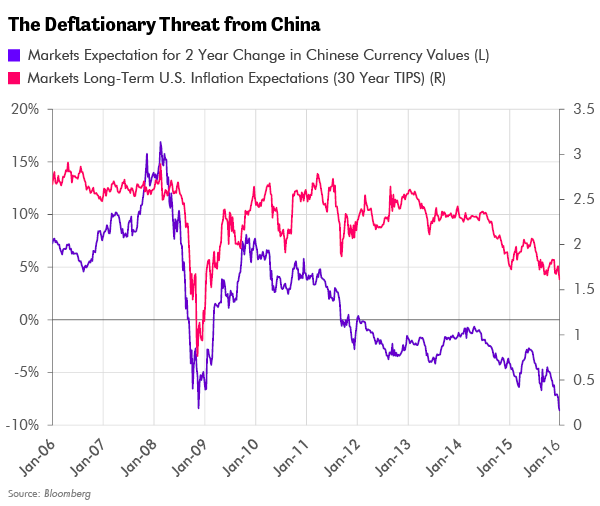

The chart below is one indicator that we can use to monitor the threat of Chinese devaluation. It shows the market’s expectation for the change in China’s currency value over a two year period versus the change in U.S. inflation expectations as expressed in the longest duration U.S. government bonds. Clearly there is a very close relationship between the two.

It’s my hypothesis that the more the market fears a deepening Chinese currency devaluation, the further U.S. inflation expectations will fall. Such a trend would reinforce the global trend of deflation now underway and could also lower global growth prospects even further from their already reduced level.

Certainly one need look no further than the example of steel to see just how devastating a meaningful currency devaluation in China would be for much of the world. Is this why the equity and credit markets seem to be so fixated upon China’s currency weakness? I believe that the answer is wholeheartedly “yes!” This is one of the chief reasons that I believe that a patiently held position in high quality, long duration bonds can be a winning investment.

As with any investment, this positioning is not without risk. The two chief risks in my opinion are 1.) much stronger global growth than I currently anticipate and 2.) a short-term spike in risk severe enough to dislocate even the safest bonds if only for a brief time. The first risk, stronger real growth, would be such a boon for so many other investments that I see limited downside to the precautionary ownership of a position in higher-quality, longer dated bonds within a diversified portfolio. The second risk, a short-term period of price weakness similar to the most extreme liquidation pressures during the height of the Global Financial Crisis, is a risk that frankly all traded assets face. I do believe strongly, however, that just as in 2008, and even earlier in 1932-1933, that any short-term weakness in the highest quality bonds would pass quickly as investors sought out the value of compelling long-term safety in an increasingly unsafe world.

In Conclusion

I do think that, whatever direction markets take, that our policy makers have the necessary tools to address these challenges. Frankly this is an optimism that I did not have back in 2008! Still, though, today’s investors face a substantial risk that the complexity of our environment may overwhelm in the short run the ability of our policy makers to identify and address the challenges we face. This raises the odds of a volatile, policy-driven “accident” such as the extreme market weakness of 1937 (“Mid Cycle Correction or Serious Downturn?” October 15, 2014).

It is more important than ever for investors to stay flexible and think rigorously about their portfolio and asset allocation. Recent currency weakness in China in particular underscores how interconnected the world’s economy and markets have become. I think it’s increasingly likely that markets have reached a point in the cycle where China’s problems are no longer isolated to it.

I continue to believe that the preponderance of risks continues to justify a cautionary and growing allocation to bonds of the highest quality and longest duration, such as U.S. government bonds. If I am right, these bonds should serve two key functions for investors within a diversified portfolio. First, they should stabilize portfolio returns by appreciating in price if markets and the economy weaken unexpectedly. Second, these bonds should serve as a pre-positioned reserve of liquid capital that investors could have at hand to deploy into compelling values that would likely arise following a challenging market. This year is definitely off to a volatile start. My confident hope is undimmed that those who have intensely studied the lessons of history should have a competitive advantage even in the most confusing of markets. •