Chief Conclusion

Key leading indicators in the commodity markets support our expectation for a mid 2017 peak in the inventory cycle. Steel offers the best insight into this cycle and the slowdown that we expect to unfold in other markets, such as credit.

In December’s Navigating Confused Seas, we noted our expectation that 2017 would likely experience a stronger first half of the year, followed by a mid-year peak in the inventory cycle. Recent events continue to support that conclusion, as we explain below.

Our optimism for the first half of 2017 was driven by a number of factors. First, rising raw material prices in China had reversed their ruinous downtrend. This upward price momentum raised China’s cost to produce steel, and therefore its price, creating a welcome higher price umbrella under which global steel markets could prosper. Second, U.S. prices were too low and needed to rise, and did so by around $100/ton in the last few weeks. We could reasonably anticipate this move as the first step in balancing supply with demand. When U.S. hot rolled coil steel prices hit a new high of almost $660/ton just a few days ago, they accomplished that goal. Finally, a glance at the calendar also suggested that we were due a peak in the cycle toward the middle of this year. The last peak took place 33 months ago, fairly deep into a cycle whose length averages 36 to 40 months.

Serpent in the Steel Paradise? Falling Chinese Raw Material Prices

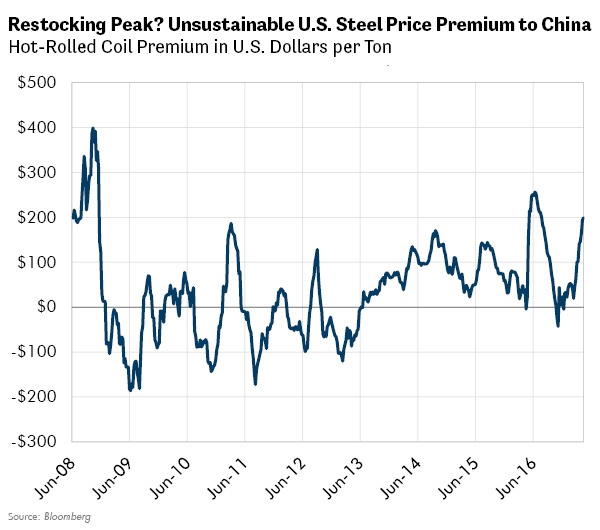

The events above, and a rapid 25% decline in Chinese raw material prices in recent days, created the preconditions for a peak we have been expecting in the steel inventory cycle, possibly even earlier than we had anticipated. Without a change in U.S. trade laws, it’s hard to see how the prevailing premium at which U.S. steel prices now trade (shown below) can be sustainable. Price declines in China, and rallies in the U.S. drove this rapid improvement. The steel cycle is a stern taskmaster, demanding that we look ahead or suffer the consequences.

The chart above illustrates, in the vernacular of the trade, that now the “arb is open” out of China, meaning that a sufficiently large arbitrage incentive exists for excess steel to flow out of China, a low priced region, into higher priced markets. This is quite a change from only several weeks ago, where no such premium existed. In the world of steel, fundamentals can change quickly, literally in the blink of an eye.

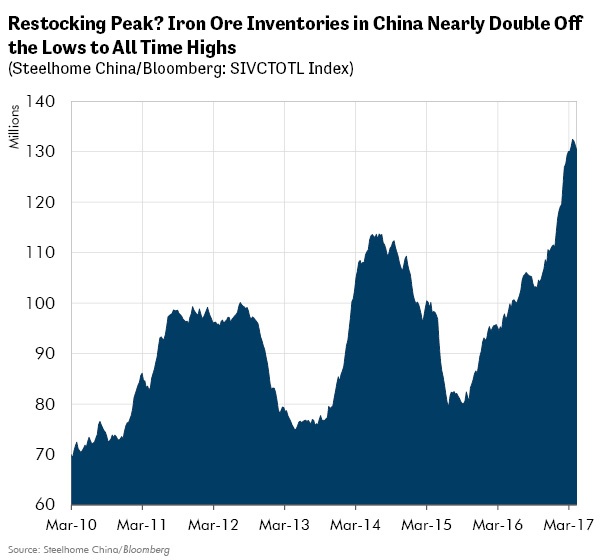

The price of iron ore, a key steel-making raw material, nearly tripled in China from late 2015. As prices rose, physical buyers and speculators engaged in the age-old practice of attempting to buy ahead of further expected price increases. Speculative “pre-buying” feeds on the shared expectation of higher prices and actually makes it happen in a self-fulfilling prophecy. Once this additional speculative demand is sated, demand falls back to levels supported by actual underlying offtake, which creates a seemingly inexplicable “air pocket” in demand that seems to arise “out of nowhere.” Evidence is mounting that we may be nearing such a point, as the chart below illustrates.

Chinese Iron Ore Inventories: Nowhere to go but Down?

Chinese iron ore inventories have risen by almost 50 million tons in the last 18 months to an all-time high north of 130 million tons. Such an enormous increase is suggestive of speculative pre-buying in this market to “get ahead” of rising iron ore prices. No doubt that this additional buying behavior was a key causal factor in actually making iron ore prices rally.

What Happens Now?

One reasonable conclusion is that recent declines in iron ore prices in China ended speculative buying. If so, the next step in the cycle is the liquidation of record high inventory levels. When such speculative buying turns to selling, the effective supply/demand balance can change instantly from an undersupplied market with rising prices to an oversupplied one with falling prices.

China’s annualized steel production in March was a staggering 800 million tons, more than eight times the size of U.S. production and a new all-time high representing nearly half the world’s steel production. The world’s steel markets simply cannot accommodate the full weight of Chinese steel exports seeking higher prices elsewhere. Something’s got to give.

One possibility is falling global steel prices in the face of sustained oversupply from China. In this scenario, Chinese steel flows outward responding to higher prices available elsewhere. Another scenario is the rise of populist driven protectionism that legislates competitive advantage through tariffs and other trade restrictions. Such a policy would elevate prices in protected regions while depressing those without similar protection.

The second approach appears very possible in the United States given that in recent days the Trump Administration announced the unprecedented use of Section 232 (passed in 1962) of the trade code directing the U.S. Department of Commerce to investigate the national security implications of higher U.S. steel imports. Assuming this investigation results in a favorable determination (a fair assumption), we could see tariffs and other such measures create a protective price umbrella under which U.S. steel producers could prosper despite the continuing menace of oversupply from China.

The U.S. consumes more steel than it produces and must import the rest of the steel it needs from overseas. Measures that restrict these imported quantities would greatly improve the fundamentals of U.S. producers.

Inventory Cycle Downturns are Global Macroeconomic Events, Stressing Many Markets at Once.

These pages have covered the theme of inventory cycles many times (Making Volatility Our Friend: Trading the Kitchin Cycle May 2014, Unsustainable Steel Premiums September 2014). These cycles, which peak and trough on average every 36 to 40 months, are examples of Rumsfeld’s “known unknowns.” We know this cycle is at work in the markets; but we don’t know exactly when it will peak; and when it will trough. As investors, we attempt to move early to avoid being hurt by the cycle, and potentially, even to profit from it.

The preconditions for a peak in the inventory cycle are now in place, just as they were in 2008, 2011, and 2014. Will the peak arrive a bit early – now only 33 months from the last peak? Or is our caution premature? Timing is the hardest part of investing. The truth is that no one can see the future.

Accordingly, we are prepared to change our portfolios in advance of events that we can reasonably anticipate. Sometimes our moves will be right. Sometimes they will be wrong. But always our goal is to move early in order to protect our clients’ wealth.

Evidence from the steel markets suggests that the odds favor a peak sooner rather than later. If so, investors should anticipate at a minimum a short-term bout of rising credit stress globally as markets price in a sudden deceleration “out of nowhere.” An inventory destocking cycle does not have to trigger a recession, although it may do so. Now is a time for investors to be alert and on guard. We certainly are.

Oftentimes a peak in the inventory cycle is nothing more than a scary and short-lived setback along the way to higher highs. But every inventory destocking cycle brings with it surprisingly scary “news” sufficient for reasonable people to wonder if we were already in a recession. Today’s markets are not priced for such a surprise which leads us to err on the side of caution.

In Conclusion

As fiduciaries, we are charged with creating portfolios robust enough to withstand downturns while continuing to thoughtfully participate in maturing markets. We attempt to do so by creating the proper mix of both stocks and bonds in a portfolio, always with an eye to mitigating negative scenarios that we may foresee. Our commitment to our clients is that we will use every tool we have learned in nearly twenty years of professional investing to act upon the results of our fundamental research to create portfolios that adhere to those goals.•